Berry Pickin' is a Chuck Berry instrumental recorded in December 1955. Chess released it as a filler on the B side of Berry's first album

After School Session and afterwards it was mainly forgotten. You won't find any discography which would list a 45rpm single containing

Berry Pickin' ... except for our

Chuck Berry Database!

This is because there indeed was a single which contains this instrumental even though only by error. Morten Reff has half a sentence about it in his "

Chuck Berry International Directory, Volume 1", but you had to read the text very carefully. Morten owns a copy of the

Berry Pickin' single, I have one, and maybe you do as well. Here's its story.

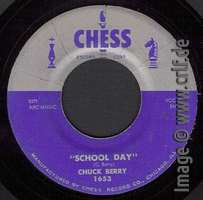

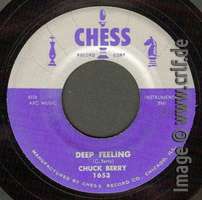

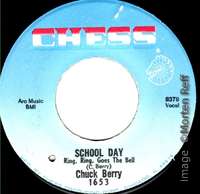

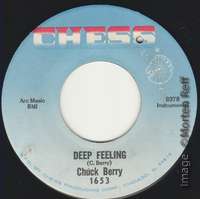

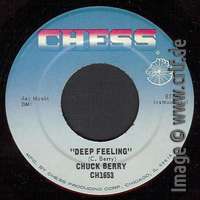

It's the story of the Chess single released in March 1957 with the catalog number 1653. One side of the record contains the song

School Day, the other side contains the instrumental

Deep Feeling.

To understand the story, we have to understand first how record production works. You'll probably know, but just in case here's a summary: Record production is a four-step process which starts in the recording studio and ends in the record pressing plant. Here the record is literally

pressed by putting a blob of plastic (polyvinyl chloride PVC or short Vinyl, once also shellac) into a pressing machine which flattens it to a disk and presses the grooves into the two surfaces. During this also the labels are firmly attached to the record. To press the grooves into the disk, you need to have a negative for each side which has the grooves elevated. This negative is called a "stamper" and made from metal to allow the pressing of thousands of records. To create a stamper you have to have a positive model of the record to produce, typically one for each side of the final disk. This positive looks like an ordinary record having the grooves engraved. It can be played on a standard turntable e.g. for testing purposes. It is not made from vinyl, though. Instead this positive typically consists of a metal kernel coated with a soft material (wax, nitrocellulose lacquer, or in the 1930s cellulose acetate). These master disks are called lacquers or acetates. A turntable-like machine cuts the grooves containing the sound into a blank lacquer which then is used in an electroplating process to create the metal stamper. The record cutter gets the sound from a master tape (at least in the era we're talking about here) which contains the final recording along with all overdubs and mixes. If you need a lot of records (such as Chess in the 1950s) it made sense to add another, intermediate step between lacquer and stamper which allows you to create many stampers for pressing in multiple presses and pressing plants. To do so, the lacquer is first transferred into a negative "father" record using electroplating. Then this "father" record is used to create multiple positive "mother" records, also known as "matrix" records (plural "matrices"). These matrices were checked and then sent out to the pressing-plants to create the stampers.

Let's go back to Chess 1653. After recording and whatever overdubs and fades were needed, the production process began with a magnetic tape containing the master recording. For identification purposes, each master tape was given a unique number. In this case, the final recording of

Deep Feeling got the number 8378 and the final recording of

School Day got 8379. Our database lists those where known. Using a record cutter both master tapes were transferred to at least two different lacquers. We know that there has been more than one lacquer as Chess 1653 was pressed both at 7-inch size to be played at 45rpm and at 10-inch size to be played at 78rpm. You needed different matrices for each obviously. The lacquer for the 7-inch 45rpm singles was electroplated into multiple mother disks or matrices. Again we know that there must have been more than one matrix, as original silver-top issues of Chess 1653 have been made from slightly different matrices.

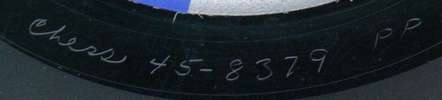

You can tell by looking at the writing in the inner "dead wax" area of the single. On some copies you find the numbers

45-8378 x and

45-8379 x engraved. This additional engraving was either hand-written on the lacquer after the grooves have been cut or - more probably - added to the mother disk after checking. The mother disk going to the

Plastic Products Co. in Memphis had a different engraving which reads

chess 45•8378 PP and

chess 45•8379 PP so the Memphis people could easily see to which label the disk belonged.

According to discogs other copies read

45-8378 Δ 15319 and

45-8379 x Δ 15318 which is the code for the Monarch Records pressing plant in Los Angeles. There are also silver-top copies where the etching reads

CH-8378 and

CH-8379, though these may be 1970s re-issues.

Note that the variety of labels known from Chess 1653 has also to do with the multitude of records needed. Some pressing plants had printers on site who created labels, some got them for external sources. But while the layout was probably given by Chess, the letter size and placement was done at the individual print shops. We know of silver-top labels having

"School Day" within quotation marks and others that don't. Also some labels had a sub-title of

(Ring! Ring! Goes The Bell) below the song name, others didn't.

After its original success Chess 1653 has been re-produced often. There are re-issues with every type of label the Chess company used during the late 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s. Up to the mid-60s these re-issues seem to have been created from the original matrices having 45-8378 and 45-8379 engraved.

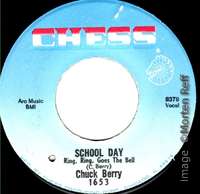

Sometime around 1965, Chess once more needed re-issues of Berry's old hits. However, they decided not to re-use the old lacquers but to create new ones from the master tapes. One reason was that the fad of the time required stereo records. So Chess tried to refresh the old mono records. They altered the sound electronically to make it sound like stereo. Judging from today, this enhancement was probably the worst they could do with the old master tapes, but they did.

This new re-issue had a light-blue label. The catalog number reads "1653" as on the original 1957 release and the correct instrumental

Deep Feeling can be heard. You can tell that new lacquers have been made by looking at the engraving of this variant. Instead of 8379 for School Day the etching erroneously reads 837

0 here.

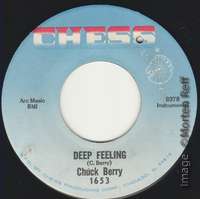

For whatever reason, only a few years later Chess once again decided to create new lacquers, probably around 1967 and with even inferior sound. Again we can tell that new lacquers were made because this next re-issue has another new etching in the "dead wax" (

8379 TM5416 CH1653 SG where

TM stands for Chess'es own Ter-Mar Pressing Plant and SG might stand for mastering engineer Geoff Sykes).

The label to this re-issue is almost identical to the light-blue one shown above. You can recognize these new ones not only by the TM text in the wax, but also by its label print. The records of this second set have the same light-blue 1960s Chess label but - most importantly - list a catalog number of "

CH 1653".

This is the interesting variant! On the B side this second light-blue re-issue not only has a different dead wax, it also has different grooves for the song!

By error someone at Ter-Mar Recording Studios took the wrong master tape to cut the new lacquer. On this B side is a Chuck Berry instrumental, but it's not

Deep Feeling! Instead they took the tape of master U7953 which is

Berry Pickin'. The faulty lacquers went into production unnoticed and records were pressed.

This must have been a time at the Chess company when somebody got totally confused over which master tapes to use for re-issues. Besides the incorrect pressing of Chess CH-1653 there exist at least two other light-blue re-issues with incorrect contents. Bo Diddley expert George White told me that he owns a light-blue re-issue of Chess 1744 (Howlin' Wolf -

The Natchez Burning b/w

You Gonna Wreck My Life) where the A side plays

I'm Going Away instead. And he knows of a light-blue re-issue of Checker 819 (Bo Diddley -

Diddley Daddy b/w

She's Fine, She's Mine) where the A side incorrectly plays

The Great Grandfather. So whoever was in charge at Chess when the light-blue re-issues were mastered, he either couldn't read or hear.

Many thanks to Morten Reff and Thierry Chanu for their tremendous help with this article!