Thursday, January 16. 2025

CHUCK100 Tribute EP Series

CHUCK100 is planned to be a series of EPs released quarterly up to what would have been Chuck Berryâs 100 birthday: 18 October 2026.

Each EP, produced by Grammy nominated Carl Nappa at the Saint Louis Recording Club, will deliver four or five covers of Chuckâs iconic hits.

The main attraction is What The Chuck consisting of Charles Berry Jr. -son (vocals, guitar), Charles Berry III -grandson (vocals, guitar), Jahi Eskridge -grandson (vocals, horns), Antonio Foster (piano), Terrence Coleman (bass) and Keith Robinson (drums).

However, itâs sometimes difficult to figure out whoâs doing the vocals on the recordings by them. There are no actual EPs or CDs, only for streaming and downloading.

âYOU NEVER CAN TELLâ #1 - 5 tracks

What The Chuck (4:07) rockânâroll

Mattie Schell (3:49) soul

Playadors featuring Steve Ewing (vocals) (4:55) reggae

Fat Pocket (4:52) funk

Mark Hochenberg (2:58) classical (instrumental)

Released: 28 September 2024

What The Chuck

Pretty ordinary but goode rockinâ version. Has a trumpet solo, guitar solo and at the end a piano solo (but not like Johnnie). What The Chuck is also contributing in some way on the other tracks below.

Mattie Schell (Compass Records) feat. Nathan Gilberg, Jackson Stokes, Ben Bicklein.

A slow soulful version. Well, itâs quite different, but becomes a little monotonous. Although she has a powerful voice.

Playadors with Steve Ewing feat. Dave Grelle, Dee Dee James, Kevin Bowers, Cody Henry, Ben Reece, Adam Hucke.

A reggae version spiced with a New Orleans touch, far from common but it works fine, and you get the feeling that everybody is having a good time.

Fat Pocket feat. Jahi Eskridge, Dan Ficocelli, Jason Hansen, Bill Henderson, Peter Shankman, Christopher Jones, Ryan Murray, Jeff Simpher, Kalonda Kay.

Donât know what it is with me and funk. It doesnât click. However, this is pretty different from any other version I have heard through the years. It has a solid beat and variations in the arrangement. Jahi Eskridge is doing the vocals.

Mark Hochberg

Now here is another treat for You Never Can Tell. The very first classical version, by the St. Louis violinist. Although at the very start it almost sounds like country(!) Different and unusual. It would have been interesting to have a whole album like this from Berryâs catalog.

âRUN RUDOLPH RUNâ #2 - 4 tracks

Fat Pocket â Run Rudolph Run (4:06) funk/soul

What The Chuck â Spending Christmas (3:30) blues

Karin Bliznik â Run Rudolph Run (4:14) smooth jazz (instrumental)

What The Chuck â Run Rudolph Run (4:39) rockânâroll

Released: Early December 2024

Fat Pocket

A soulful rendition with a funky sound.

Karin Bliznik

A trumpet player in the jazz field. Pretty unusual version with a few vocal lines in between. I always enjoy when people are finding their own approach to the tune. And this IS different.

What The Chuck

rocks pretty goode on the last track even using the same ending as the original, although not faded.

And interesting to have a version of the obscure Berry song âSpending Christmasâ, originally recorded 15 December 1964, a song also known as My Blue Christmas. (Berry's version was first released in 2009 on the Hip-O Select box-set âYou Never Can Tell â His Complete Recordings 1960-1966â.) But unfortunately the vocals are pretty uninspired. Okay, itâs following the original in that sense but it becomes a little boring anyway, unfortunately like Chuckâs own.

(To give you an idea, on the 15 December â64 session 8 track were recorded: Lonely Schooldays (slow version), His Daughter Caroline (slow version), Dear Dad, I Want To Be You Driver, Spending Christmas (2 versions), The Song Of My Love and Butterscotch.)

Another project for the Chuck100 is a special Tribute album by national and international artists which should see the light of day in 2026. Also an upcoming collaboration with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra.

The Berry family is also working with Revelations Entertainment, a production company founded by Morgan Freeman and Lori McCreary, which optioned the rights to Chuck Berryâs Life Story. They are developing a drama series that would trace Berryâs progress from St. Louis to worldwide stardom.

So it seems we have a lot to look forward to in the coming months of 2025 and 2026.

Each EP, produced by Grammy nominated Carl Nappa at the Saint Louis Recording Club, will deliver four or five covers of Chuckâs iconic hits.

The main attraction is What The Chuck consisting of Charles Berry Jr. -son (vocals, guitar), Charles Berry III -grandson (vocals, guitar), Jahi Eskridge -grandson (vocals, horns), Antonio Foster (piano), Terrence Coleman (bass) and Keith Robinson (drums).

However, itâs sometimes difficult to figure out whoâs doing the vocals on the recordings by them. There are no actual EPs or CDs, only for streaming and downloading.

âYOU NEVER CAN TELLâ #1 - 5 tracks

What The Chuck (4:07) rockânâroll

Mattie Schell (3:49) soul

Playadors featuring Steve Ewing (vocals) (4:55) reggae

Fat Pocket (4:52) funk

Mark Hochenberg (2:58) classical (instrumental)

Released: 28 September 2024

What The Chuck

Pretty ordinary but goode rockinâ version. Has a trumpet solo, guitar solo and at the end a piano solo (but not like Johnnie). What The Chuck is also contributing in some way on the other tracks below.

Mattie Schell (Compass Records) feat. Nathan Gilberg, Jackson Stokes, Ben Bicklein.

A slow soulful version. Well, itâs quite different, but becomes a little monotonous. Although she has a powerful voice.

Playadors with Steve Ewing feat. Dave Grelle, Dee Dee James, Kevin Bowers, Cody Henry, Ben Reece, Adam Hucke.

A reggae version spiced with a New Orleans touch, far from common but it works fine, and you get the feeling that everybody is having a good time.

Fat Pocket feat. Jahi Eskridge, Dan Ficocelli, Jason Hansen, Bill Henderson, Peter Shankman, Christopher Jones, Ryan Murray, Jeff Simpher, Kalonda Kay.

Donât know what it is with me and funk. It doesnât click. However, this is pretty different from any other version I have heard through the years. It has a solid beat and variations in the arrangement. Jahi Eskridge is doing the vocals.

Mark Hochberg

Now here is another treat for You Never Can Tell. The very first classical version, by the St. Louis violinist. Although at the very start it almost sounds like country(!) Different and unusual. It would have been interesting to have a whole album like this from Berryâs catalog.

âRUN RUDOLPH RUNâ #2 - 4 tracks

Fat Pocket â Run Rudolph Run (4:06) funk/soul

What The Chuck â Spending Christmas (3:30) blues

Karin Bliznik â Run Rudolph Run (4:14) smooth jazz (instrumental)

What The Chuck â Run Rudolph Run (4:39) rockânâroll

Released: Early December 2024

Fat Pocket

A soulful rendition with a funky sound.

Karin Bliznik

A trumpet player in the jazz field. Pretty unusual version with a few vocal lines in between. I always enjoy when people are finding their own approach to the tune. And this IS different.

What The Chuck

rocks pretty goode on the last track even using the same ending as the original, although not faded.

And interesting to have a version of the obscure Berry song âSpending Christmasâ, originally recorded 15 December 1964, a song also known as My Blue Christmas. (Berry's version was first released in 2009 on the Hip-O Select box-set âYou Never Can Tell â His Complete Recordings 1960-1966â.) But unfortunately the vocals are pretty uninspired. Okay, itâs following the original in that sense but it becomes a little boring anyway, unfortunately like Chuckâs own.

(To give you an idea, on the 15 December â64 session 8 track were recorded: Lonely Schooldays (slow version), His Daughter Caroline (slow version), Dear Dad, I Want To Be You Driver, Spending Christmas (2 versions), The Song Of My Love and Butterscotch.)

Another project for the Chuck100 is a special Tribute album by national and international artists which should see the light of day in 2026. Also an upcoming collaboration with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra.

The Berry family is also working with Revelations Entertainment, a production company founded by Morgan Freeman and Lori McCreary, which optioned the rights to Chuck Berryâs Life Story. They are developing a drama series that would trace Berryâs progress from St. Louis to worldwide stardom.

So it seems we have a lot to look forward to in the coming months of 2025 and 2026.

Friday, January 12. 2024

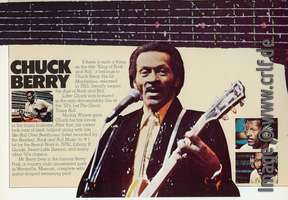

Chuck Berry in Fake Stereo

As you know from the long article âChuck Berry in Stereoâ on this blog, all of Berryâs great hits from the 1950s were recorded and released as pure Mono. No multi-track studio tapes exist nor any two-track stereo releases.

In the second half of the 1960s, with the popularity of Stereo albums and FM radio, Mono records sounded outdated and dull. Record companies trying to re-sell 1950s hits therefore used a trick to create fake stereo versions of recordings originally made and only available in Mono.

The old recordings were âelectronically reprocessed for stereoâ. Technically the original mono signal was copied to both stereo channels. On one channel the higher tones were enhanced, on the other the lower tones. One channel was delayed a tiny fraction of a second and artificial echo and reverb were used to mask this delay. Unfortunately this distorts the original recording to an amount which makes them sound ugly when compared to the original mono mix.

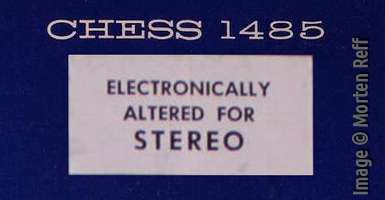

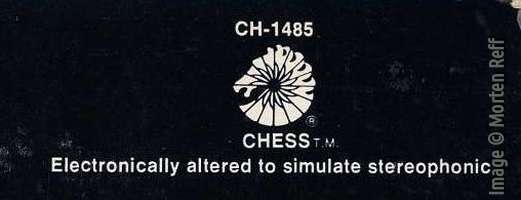

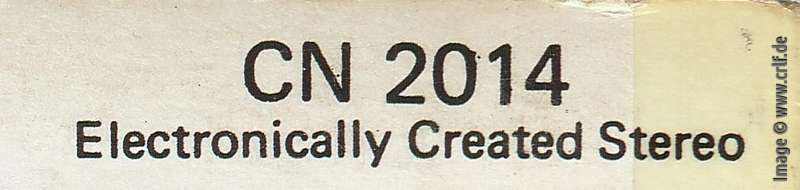

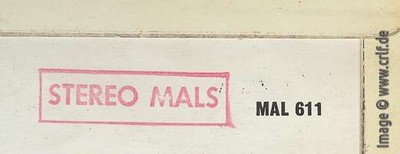

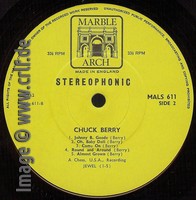

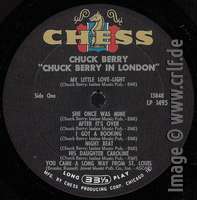

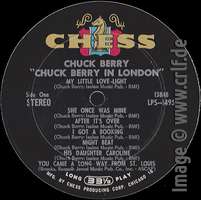

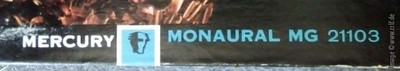

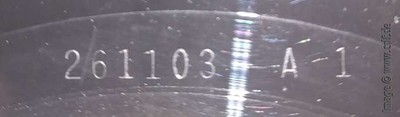

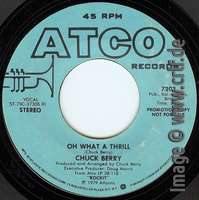

During the 1970s many re-issues of Berry material contained such fake stereo which is why record collectors omit them to the most part. At least some of the fake stereo releases came with a tiny warning as shown in these cover segments.

If you were following the hype around the Beatlesâ ânewâ recording âNow and Thenâ, you learned that nowadays computers are able to separate John Lennonâs piano playing from his singing based on a source tape where these two blend into each other. The trick is to find notes and frequencies which are typical to a male singer and to find notes and frequencies which are typical to a piano. A human listener can do so easily and tell exactly what is singing and what is piano playing. Computers are not that good.

However, new computer techniques approximate the identification of a songâs parts. The trick is to have a computer analyze thousands or millions of piano recordings and to find patterns which are typical to piano playing. This is pure statistics, technically called machine learning, or for the marketing folks âartificial intelligenceâ. Given enough training data, you can teach the software to identify piano playing, male or female vocals, drums, guitar, saxes, and so on.

There is free and commercial software available which does a pretty good job at identifying and separating instruments from a recording mix. However, such a result is never perfect. Even a human listener might get fooled, when a talented vocalist mimics a saxophone solo. Certain sounds can be created using different instruments alike such as a bass line played on the lower strings of a guitar. Especially pianos are difficult to identify as they have a very wide range of tones which can sound like a guitar or even like some drum set segments. And of course it is very hard to separate two guitars or two pianos.

If you separate the musical instruments used during the original recording, you can re-use the extracted tracks to combine them with other recordings just like they did with the Beatles song. Or you can re-mix the individual elements at varying intensities and delays to two separate tracks which build the left and right channel of a stereo release.

Hit Parade Records of Canada for some time already uses this re-stereofication method to create fake stereo versions of 1950s hits. A first fake stereo version of a Berry hit (âSweet Little Sixteenâ) appeared in 2020.

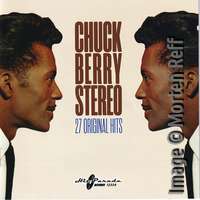

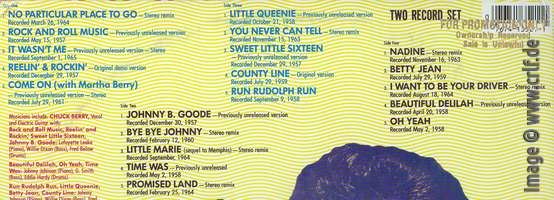

In 2023 Hit Parade Records released the CD album âChuck Berry Stereo: 27 Original Hitsâ containing 22 of such fake stereo versions. The other five songs are stereo versions originally released on the 1960s Chess albums. âRoute 66â is fake stereo, even though a true stereo recording of an alternative take exists.

The CD cover does not mention the artificial nature of the versions. This âfakeâ aspect is hidden on the last page of the booklet.

So now we can listen to songs such as âMaybelleneâ or âJohnny B. Goodeâ in stereo. And just like in the 1970s, these fake stereo versions are much worse than the original releases. For the most part we hear the lead guitar at one end of the stereo range and the cymbals from the drum set at the opposite end. Everything else is more or less in the center with the vocals quite low in the mix. The marketing material shouts that ânow you can hear guitar notes come to life that were previously buried in the mono mixesâ but this goes with the consequence of other elements now getting buried instead.

As said, given the original mixed material a separation cannot be perfect. Here we hear notes from the same guitar sometimes from the left, sometimes from the center, sometimes even from the complete other side of the room which sounds as if there were more guitars present in the studio as there really were. On the other hand it sounds as if there were only cymbals on the drum kit but no drums at all, a woolly sound on the drums altogether. And especially problematic is the piano, which sounds as if it were moved around the studio during a songâs recording take. In general there is too much echo just like it were with the 1970s fake stereo releases. One positive note, though: What they did really good was the separation of Berryâs lead vocal and the chorus on âAlmost Grownâ. This sounds as if the vocal group is standing to the side as it probably was originally.

All in all these versions are nothing a collector would want. On the contrary: just as in the 1970s, where the original mono recordings were replaced by the fake âelectronic stereoâ variants, the same also applies here. As soon as streaming services or re-issuers learn of the existence of these so-called âtrueâ stereo versions, how long will it be before the original mono versions are replaced?

Morten Reff adds: âJust to compare a little. I also bought the new âChirping Cricketsâ (the first LP by Buddy Holly And The Crickets from 1958) on Rollercoaster Records in âstereoâ, and they did a much better job of it. Clearer and better sound and better stereo effect. Although I must admit that I still go for the original mono versions.â

In the second half of the 1960s, with the popularity of Stereo albums and FM radio, Mono records sounded outdated and dull. Record companies trying to re-sell 1950s hits therefore used a trick to create fake stereo versions of recordings originally made and only available in Mono.

The old recordings were âelectronically reprocessed for stereoâ. Technically the original mono signal was copied to both stereo channels. On one channel the higher tones were enhanced, on the other the lower tones. One channel was delayed a tiny fraction of a second and artificial echo and reverb were used to mask this delay. Unfortunately this distorts the original recording to an amount which makes them sound ugly when compared to the original mono mix.

During the 1970s many re-issues of Berry material contained such fake stereo which is why record collectors omit them to the most part. At least some of the fake stereo releases came with a tiny warning as shown in these cover segments.

Cover details of 1970s fake stereo releases

If you were following the hype around the Beatlesâ ânewâ recording âNow and Thenâ, you learned that nowadays computers are able to separate John Lennonâs piano playing from his singing based on a source tape where these two blend into each other. The trick is to find notes and frequencies which are typical to a male singer and to find notes and frequencies which are typical to a piano. A human listener can do so easily and tell exactly what is singing and what is piano playing. Computers are not that good.

However, new computer techniques approximate the identification of a songâs parts. The trick is to have a computer analyze thousands or millions of piano recordings and to find patterns which are typical to piano playing. This is pure statistics, technically called machine learning, or for the marketing folks âartificial intelligenceâ. Given enough training data, you can teach the software to identify piano playing, male or female vocals, drums, guitar, saxes, and so on.

There is free and commercial software available which does a pretty good job at identifying and separating instruments from a recording mix. However, such a result is never perfect. Even a human listener might get fooled, when a talented vocalist mimics a saxophone solo. Certain sounds can be created using different instruments alike such as a bass line played on the lower strings of a guitar. Especially pianos are difficult to identify as they have a very wide range of tones which can sound like a guitar or even like some drum set segments. And of course it is very hard to separate two guitars or two pianos.

If you separate the musical instruments used during the original recording, you can re-use the extracted tracks to combine them with other recordings just like they did with the Beatles song. Or you can re-mix the individual elements at varying intensities and delays to two separate tracks which build the left and right channel of a stereo release.

Hit Parade Records of Canada for some time already uses this re-stereofication method to create fake stereo versions of 1950s hits. A first fake stereo version of a Berry hit (âSweet Little Sixteenâ) appeared in 2020.

In 2023 Hit Parade Records released the CD album âChuck Berry Stereo: 27 Original Hitsâ containing 22 of such fake stereo versions. The other five songs are stereo versions originally released on the 1960s Chess albums. âRoute 66â is fake stereo, even though a true stereo recording of an alternative take exists.

The CD cover does not mention the artificial nature of the versions. This âfakeâ aspect is hidden on the last page of the booklet.

So now we can listen to songs such as âMaybelleneâ or âJohnny B. Goodeâ in stereo. And just like in the 1970s, these fake stereo versions are much worse than the original releases. For the most part we hear the lead guitar at one end of the stereo range and the cymbals from the drum set at the opposite end. Everything else is more or less in the center with the vocals quite low in the mix. The marketing material shouts that ânow you can hear guitar notes come to life that were previously buried in the mono mixesâ but this goes with the consequence of other elements now getting buried instead.

As said, given the original mixed material a separation cannot be perfect. Here we hear notes from the same guitar sometimes from the left, sometimes from the center, sometimes even from the complete other side of the room which sounds as if there were more guitars present in the studio as there really were. On the other hand it sounds as if there were only cymbals on the drum kit but no drums at all, a woolly sound on the drums altogether. And especially problematic is the piano, which sounds as if it were moved around the studio during a songâs recording take. In general there is too much echo just like it were with the 1970s fake stereo releases. One positive note, though: What they did really good was the separation of Berryâs lead vocal and the chorus on âAlmost Grownâ. This sounds as if the vocal group is standing to the side as it probably was originally.

All in all these versions are nothing a collector would want. On the contrary: just as in the 1970s, where the original mono recordings were replaced by the fake âelectronic stereoâ variants, the same also applies here. As soon as streaming services or re-issuers learn of the existence of these so-called âtrueâ stereo versions, how long will it be before the original mono versions are replaced?

Morten Reff adds: âJust to compare a little. I also bought the new âChirping Cricketsâ (the first LP by Buddy Holly And The Crickets from 1958) on Rollercoaster Records in âstereoâ, and they did a much better job of it. Clearer and better sound and better stereo effect. Although I must admit that I still go for the original mono versions.â

Monday, March 13. 2023

Little Queenie overdubs

On this site we maintain a database containing all Chuck Berry recordings ever published on CD or Vinyl. We welcome every user comment enhancing the correctness of the data listed, such as reader Martyâs recent email regarding the recording of Little Queenie:

As even Odie Payne couldnât play a two-handed drum fill and a cymbal in parallel, this is a very valid comment. Martyâs email triggered some in-depth investigations and a huge number of emails floating between the contributors to this site.

Todayâs technical possibilities allow you to extract, modify and single out parts of a historical recording. This allowed our technical expert Arne Wolfswinkel to both verify Martyâs findings and to discover some additional astonishing facts.

You should know that besides the original 1958 record release we have another, slightly different take of Berryâs classic tune. This âpreviously unreleased versionâ (later called âTake 8â) of Little Queenie came into light in 1986, when Steve Hoffman presented to us lost recordings from the vaults of Chess Records. (âRockânâRoll Raritiesâ, CHESS CH2-92521)

Overdubbing was a common practice with Chuck Berryâs recordings at Jack Wienerâs Sheldon Recording Studios. That way the producers could add more Chuck Berry guitar to a recording or more Chuck Berry voice. Even a classic such as Johnny B. Goode was created in such a two-step process. (See the blog article âThe Johnny B. Goode Sessionâ)

Overdubbing means that a first recording was made using the full band. During recording, Berry played some of the guitar elements and sung the main vocal. Later the engineer and Berry worked out the finer details such as additional guitar solos or a second voice without the need of the band. The engineer played back a tape containing the original base track, Berry sang or played, and the result was recorded to a second tape. This procedure was necessary, because in the 1950s Chess could not record multiple instruments separately and mix them later.

One example for a guitar and vocal overdub is take 9A of Merry Christmas Baby from the Little Queenie session. This is the variant released on Chess single 1714.

With Little Queenie this overdubbing happened a bit differently. As Marty found, some parts of the drums were recorded for the base track while other parts were recorded during the overdub. And comparing the two slightly different takes of Little Queenie which survived, it becomes obvious that in this session the overdubbing involved not just Berry or Odie Payne, but also Lafayette Leake.

Both takes of Little Queenie are based on the same base track which consists of Berry playing rhythm guitar, Willie Dixon playing double bass and Odie Payne playing the drum rhythm. This base track is 100% identical on both takes.

Different, and thus overdubbed onto this base track, is Berryâs singing, some additional guitar playing, Odie Payneâs cymbal or hi-hat, and Lafayette Leakeâs piano. As due to sound degeneration overdubbing was reasonable only onto the first-generation tape, we have to imagine that Berry, Payne, and Leake on this 19th November 1958 were listening to the base track and together added their overdubs.

The correct recording details for both takes of Little Queenie will therefore be:

We will alter our database accordingly. We will keep the âTake 8â distinction for the alternative even though it is completely unclear where it comes from. The count-in preceding the song (âAre you ready, Chuck?â) on the 1986 album is probably not from the original tape as the guitar intro overlaps the engineerâs announcement which would usually result in an immediate stop to the recording. It is known that Steve Hoffman shuffled such segments around and even created completely new songs from segments of different takes. (For details, read the blog posts âSweet Little Eight Variants of Sweet Little Sixteenâ and âChuck Berry in Stereoâ)

[addition 08.01.2024: Those who know have found that the take 8 introduction has been taken by Steve Hoffman from a tape containing the recording takes of Sweet Little Rock and Roller.]

Run Rudolph Run from the same session uses the same melody and the same rhythm as Little Queenie. And here as well we hear both a guitar overdub and additional cymbal or hi-hat playing.

We would like to thank reader Marty for finding the cymbal overdub and especially for telling us.

We believe thereâs a ride cymbal over dub on the original version, what do you think? Because you can hear drum fills and the ride cymbal continues.

As even Odie Payne couldnât play a two-handed drum fill and a cymbal in parallel, this is a very valid comment. Martyâs email triggered some in-depth investigations and a huge number of emails floating between the contributors to this site.

Todayâs technical possibilities allow you to extract, modify and single out parts of a historical recording. This allowed our technical expert Arne Wolfswinkel to both verify Martyâs findings and to discover some additional astonishing facts.

You should know that besides the original 1958 record release we have another, slightly different take of Berryâs classic tune. This âpreviously unreleased versionâ (later called âTake 8â) of Little Queenie came into light in 1986, when Steve Hoffman presented to us lost recordings from the vaults of Chess Records. (âRockânâRoll Raritiesâ, CHESS CH2-92521)

Overdubbing was a common practice with Chuck Berryâs recordings at Jack Wienerâs Sheldon Recording Studios. That way the producers could add more Chuck Berry guitar to a recording or more Chuck Berry voice. Even a classic such as Johnny B. Goode was created in such a two-step process. (See the blog article âThe Johnny B. Goode Sessionâ)

Overdubbing means that a first recording was made using the full band. During recording, Berry played some of the guitar elements and sung the main vocal. Later the engineer and Berry worked out the finer details such as additional guitar solos or a second voice without the need of the band. The engineer played back a tape containing the original base track, Berry sang or played, and the result was recorded to a second tape. This procedure was necessary, because in the 1950s Chess could not record multiple instruments separately and mix them later.

One example for a guitar and vocal overdub is take 9A of Merry Christmas Baby from the Little Queenie session. This is the variant released on Chess single 1714.

With Little Queenie this overdubbing happened a bit differently. As Marty found, some parts of the drums were recorded for the base track while other parts were recorded during the overdub. And comparing the two slightly different takes of Little Queenie which survived, it becomes obvious that in this session the overdubbing involved not just Berry or Odie Payne, but also Lafayette Leake.

Both takes of Little Queenie are based on the same base track which consists of Berry playing rhythm guitar, Willie Dixon playing double bass and Odie Payne playing the drum rhythm. This base track is 100% identical on both takes.

Different, and thus overdubbed onto this base track, is Berryâs singing, some additional guitar playing, Odie Payneâs cymbal or hi-hat, and Lafayette Leakeâs piano. As due to sound degeneration overdubbing was reasonable only onto the first-generation tape, we have to imagine that Berry, Payne, and Leake on this 19th November 1958 were listening to the base track and together added their overdubs.

The correct recording details for both takes of Little Queenie will therefore be:

Chuck Berry guitar, vocal (overdub), 2nd guitar (overdub)

Ellis "Lafayette" Leake piano (overdub)

Willie Dixon double bass

Odie Payne drums, additional drums (overdub)

We will alter our database accordingly. We will keep the âTake 8â distinction for the alternative even though it is completely unclear where it comes from. The count-in preceding the song (âAre you ready, Chuck?â) on the 1986 album is probably not from the original tape as the guitar intro overlaps the engineerâs announcement which would usually result in an immediate stop to the recording. It is known that Steve Hoffman shuffled such segments around and even created completely new songs from segments of different takes. (For details, read the blog posts âSweet Little Eight Variants of Sweet Little Sixteenâ and âChuck Berry in Stereoâ)

[addition 08.01.2024: Those who know have found that the take 8 introduction has been taken by Steve Hoffman from a tape containing the recording takes of Sweet Little Rock and Roller.]

Run Rudolph Run from the same session uses the same melody and the same rhythm as Little Queenie. And here as well we hear both a guitar overdub and additional cymbal or hi-hat playing.

We would like to thank reader Marty for finding the cymbal overdub and especially for telling us.

Tuesday, January 31. 2023

Lonely School Days - the variants explained

Several Chuck Berry songs have been recorded multiple times - not only live, but also in the studio.

Sometimes a second recording was made for commercial reasons, e.g. when a new record company tried to generate additional income from old songs. A typical example is Roll Over Beethoven, initially recorded in 1956 in Chicago for Chess Records, re-recorded 1966 in Clayton for Mercury Records.

Sometimes a second recording was made for artistic reasons when Berry tried to make a song sound better or at least different. See for instance Havana Moon, initially recorded in 1956, then in 1979, and finally in the late 1990s.

In addition, songs evolve over time during the recording process itself until a final version pleases both artist and company. See for instance the song recorded as 21 (Twenty-One) of which some studio tapes survived. There are fairly different variants until a final result was reached and published under the title Vacation Time.

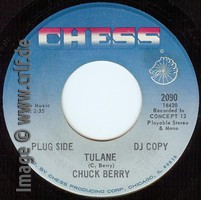

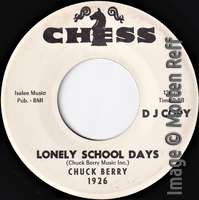

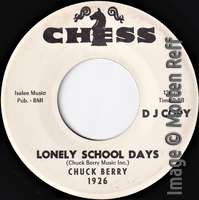

Lonely School Days is another song which evolved over time. One surviving variant has been recorded in late 1964 and released on the back of Chess single 1926, Dear Dad, published in March 1965. This variant is a slow, emotional song. It can be easily identified by the prominent use of a sax, probably played by Bill Hamilton. This variant is almost three minutes long and commonly referred to as the "Slow Version".

B side of CHESS single 1926 (DJ Copy)

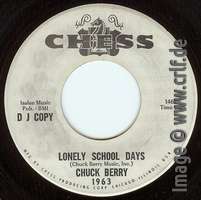

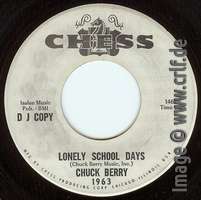

Somebody really liked this song. Just one and a half years later it made it again to the song list of a recording session. In the spring of 1966, a second variant of Lonely School Days was cut. This time it had no sax, but more guitars. Most importantly it was much more rocking, played much faster. Singing the same song at much higher speed reduces the run length to a little over 2:30 minutes.

Surprisingly, this "Fast Version" immediately was used again as the B side of a Chess single. Chess 1963 having Ramona, Say Yes on the plug side was released in June 1966. So we have two Chess singles, released not far apart, having the same song in two different versions.

B side of CHESS single 1963 (DJ Copy)

Soon after the release of the second single, Chuck Berry left Chess Records to work for Mercury. The "Slow Version" never made it to a contemporary album. Only in the late eighties and nineties it was found on some rare LP albums.

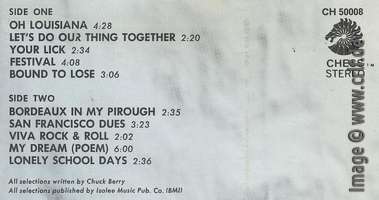

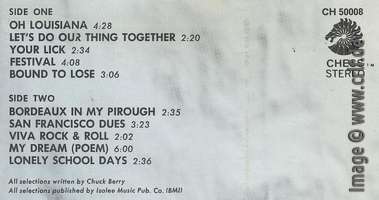

However, the "Fast Version" was included on an official Chess album: San Francisco Dues (Chess 50008) was published in 1971, five years after the song's initial release. Berry had returned to Chess and to fill his second new album a few recordings were added which had not made it to LPs before. Interestingly the LP contained a Stereo mix of the "Fast Version" while both singles had been in Mono - as were all Chess singles in the 1960s.

This is the track listing from the back of San Francisco Dues (Chess 50008) containing the Stereo mix of the shorter, fast version.

Remember: San Francisco Dues contained the Stereo mix of the "Fast Version". Simple, isn't it?

However, who listens to Vinyl albums any more? If you listen to San Francisco Dues from one of the streaming services, Lonely School Days isn't fast at all. Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube all play the "Slow Version" as part of San Francisco Dues. Due to this a reader recently emailed and wanted us to correct our database of all Chuck Berry recordings. We are happy for every hint or correction, but here we refused to do any changes, as our listing is correct!

How can it happen that online services play the wrong song - all of them alike? This is due to how they get their playing lists. Record labels such as Universal provide the streaming platforms with the files to play. If the record company is in error, so are all their customers.

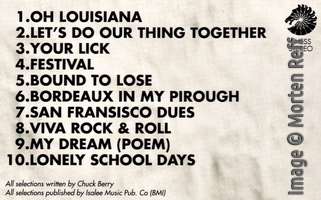

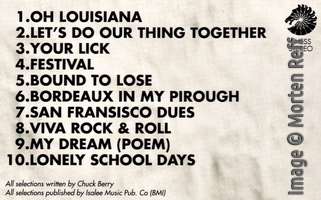

We assume that this specific error was introduced as early as 2013. That year Universal in the U.S. published a CD re-release of San Francisco Dues (Geffen GET-54058-CD). And on this re-release they included the wrong variant of Lonely School Days. Morten Reff noticed this and complained about it in his review on this blog soon thereafter. It was not the only thing to complain about: Over and over on label, box, and booklet the company managed to spell "San Fransisco" with an s! One really has to wonder about quality control at Universal.

This is the track listing from the back of Geffen's CD re-issue of San Francisco Dues (Geffen GET-54058-CD) containing the wrong version. Note the mis-spelling of San Francisco and the missing run lengths.

Universal in Japan did a much better job with their re-release of San Francisco Dues (Geffen UICY-94635). They not only included the correct "Fast Version" where it belonged, they also added three bonus tracks: the "Slow Version" in Mono and two different mixes of Ramona, Say Yes.

Moral of the story: In today's digital world errors reproduce fast and are hard to correct. Always double-check with a reliable source.

Many thanks to reader Andy for pointing us to the error in the streaming services - though not for complaining about our database

[Addition by reader Andy: "I should mention that my initial email was actually a failed attempt at correction rather than a complaint. Why would I ever complain about so meticulous and thorough a database regarding one of my favorite artists? Keep up the good work."]

Sometimes a second recording was made for commercial reasons, e.g. when a new record company tried to generate additional income from old songs. A typical example is Roll Over Beethoven, initially recorded in 1956 in Chicago for Chess Records, re-recorded 1966 in Clayton for Mercury Records.

Sometimes a second recording was made for artistic reasons when Berry tried to make a song sound better or at least different. See for instance Havana Moon, initially recorded in 1956, then in 1979, and finally in the late 1990s.

In addition, songs evolve over time during the recording process itself until a final version pleases both artist and company. See for instance the song recorded as 21 (Twenty-One) of which some studio tapes survived. There are fairly different variants until a final result was reached and published under the title Vacation Time.

Lonely School Days is another song which evolved over time. One surviving variant has been recorded in late 1964 and released on the back of Chess single 1926, Dear Dad, published in March 1965. This variant is a slow, emotional song. It can be easily identified by the prominent use of a sax, probably played by Bill Hamilton. This variant is almost three minutes long and commonly referred to as the "Slow Version".

B side of CHESS single 1926 (DJ Copy)

Somebody really liked this song. Just one and a half years later it made it again to the song list of a recording session. In the spring of 1966, a second variant of Lonely School Days was cut. This time it had no sax, but more guitars. Most importantly it was much more rocking, played much faster. Singing the same song at much higher speed reduces the run length to a little over 2:30 minutes.

Surprisingly, this "Fast Version" immediately was used again as the B side of a Chess single. Chess 1963 having Ramona, Say Yes on the plug side was released in June 1966. So we have two Chess singles, released not far apart, having the same song in two different versions.

B side of CHESS single 1963 (DJ Copy)

Soon after the release of the second single, Chuck Berry left Chess Records to work for Mercury. The "Slow Version" never made it to a contemporary album. Only in the late eighties and nineties it was found on some rare LP albums.

However, the "Fast Version" was included on an official Chess album: San Francisco Dues (Chess 50008) was published in 1971, five years after the song's initial release. Berry had returned to Chess and to fill his second new album a few recordings were added which had not made it to LPs before. Interestingly the LP contained a Stereo mix of the "Fast Version" while both singles had been in Mono - as were all Chess singles in the 1960s.

This is the track listing from the back of San Francisco Dues (Chess 50008) containing the Stereo mix of the shorter, fast version.

Remember: San Francisco Dues contained the Stereo mix of the "Fast Version". Simple, isn't it?

However, who listens to Vinyl albums any more? If you listen to San Francisco Dues from one of the streaming services, Lonely School Days isn't fast at all. Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube all play the "Slow Version" as part of San Francisco Dues. Due to this a reader recently emailed and wanted us to correct our database of all Chuck Berry recordings. We are happy for every hint or correction, but here we refused to do any changes, as our listing is correct!

How can it happen that online services play the wrong song - all of them alike? This is due to how they get their playing lists. Record labels such as Universal provide the streaming platforms with the files to play. If the record company is in error, so are all their customers.

We assume that this specific error was introduced as early as 2013. That year Universal in the U.S. published a CD re-release of San Francisco Dues (Geffen GET-54058-CD). And on this re-release they included the wrong variant of Lonely School Days. Morten Reff noticed this and complained about it in his review on this blog soon thereafter. It was not the only thing to complain about: Over and over on label, box, and booklet the company managed to spell "San Fransisco" with an s! One really has to wonder about quality control at Universal.

This is the track listing from the back of Geffen's CD re-issue of San Francisco Dues (Geffen GET-54058-CD) containing the wrong version. Note the mis-spelling of San Francisco and the missing run lengths.

Universal in Japan did a much better job with their re-release of San Francisco Dues (Geffen UICY-94635). They not only included the correct "Fast Version" where it belonged, they also added three bonus tracks: the "Slow Version" in Mono and two different mixes of Ramona, Say Yes.

Moral of the story: In today's digital world errors reproduce fast and are hard to correct. Always double-check with a reliable source.

Many thanks to reader Andy for pointing us to the error in the streaming services - though not for complaining about our database

[Addition by reader Andy: "I should mention that my initial email was actually a failed attempt at correction rather than a complaint. Why would I ever complain about so meticulous and thorough a database regarding one of my favorite artists? Keep up the good work."]

Sunday, January 29. 2023

An Interview with Johnnie Johnson - 1987

On July 5th, 1987 Chuck Berry performed in BĂ„stad, Sweden.

This site's contributor Morten Reff and the Berry fans Johan Hasselberg and Thomas Einarsson had the opportunity to talk to Johnnie Johnson, long-time partner and pianist for Chuck Berry. Thanks to Morten and Johan we can reprint the questions and answers.

Left to right: Morten Reff, Johnnie Johnson, Thomas Einarsson, Johan Hasselberg, and Herman Jackson at the Park Hotel in BĂ„stad, Sweden, July 5, 1987. Herman was Chuck Berry's drummer during the summer 1987 tour. Thomas had done a painting by Chuck Berry that he handed over to Johnnie Johnson.

Photo: Carl Hasselberg

The interview is made over a cup of coffee at the hotel's outdoor seating. Johnnie takes a big chunk of coffee and starts telling about himself:

DID YOU PLAY MOSTLY RHYTHM & BLUES?

WHAT PIANISTS DID YOU LISTEN TO AT THIS TIME?

HOW DID YOU TO GET IN CONTACT WITH CHUCK BERRY?

Chuck Berry in concert, Norrvikens TrÀdgÄrdar, BÄstad, Sweden, July 5, 1987

Photo: Johan Hasselberg

WHO PLAYED THE SAXOPHONE IN THE JOHNNIE JOHNSON TRIO?

WAS IT A BASS PLAYER IN THE BAND?

CHANGED THE BAND NAME WHEN CHUCK CAME?

Left to right: Chuck Berry, George French, Johnnie Johnson in concert, Norrvikens TrÀdgÄrdar, BÄstad, Sweden, July 5, 1987

Photo: Bo Berglind

YOU PLAY A MELODY ON THE PIANO ON MANY OF CHUCK BERRY'S SONGS.

IT WORKS AS A SOLO INSTRUMENT.

DO YOU STILL PLAY IN THE CLUBS IN ST. LOUIS?

DO YOU PLAY ALONE OR DO YOU HAVE A BAND?

WHAT REPERTOIRE DO YOU HAVE?

DO YOU EVEN SING?

YOU HAVE BEEN AWARDED A DISTINCTION AT ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME.

THANK YOU, JOHNNIE !!

And, Johan tells, they met again: "Johnnie gave me his address and two years later I greeted him in St. Louis, and listened to Johnnie Johnson & The Magnificent Four."

Many thanks to Morten and Johan for sharing these memories with us!

This site's contributor Morten Reff and the Berry fans Johan Hasselberg and Thomas Einarsson had the opportunity to talk to Johnnie Johnson, long-time partner and pianist for Chuck Berry. Thanks to Morten and Johan we can reprint the questions and answers.

Left to right: Morten Reff, Johnnie Johnson, Thomas Einarsson, Johan Hasselberg, and Herman Jackson at the Park Hotel in BĂ„stad, Sweden, July 5, 1987. Herman was Chuck Berry's drummer during the summer 1987 tour. Thomas had done a painting by Chuck Berry that he handed over to Johnnie Johnson.

Photo: Carl Hasselberg

The interview is made over a cup of coffee at the hotel's outdoor seating. Johnnie takes a big chunk of coffee and starts telling about himself:

I was born in West Virginia on July 8, 1924. When I went to school I played piano, drums, and bass. But piano was my main instrument. I was in a High School band until 1943, when I started my military service at the navy. When I pulled out in 1946, I started my first own band. In 1949 I moved to Chicago, and then on to St. Louis.

DID YOU PLAY MOSTLY RHYTHM & BLUES?

Well, most of the time there were nothing but standard songs, such as "Stardust", "Body and Soul", Sunny Side of the Street", or whatever. It was before this rhythm & blues breakthrough.

WHAT PIANISTS DID YOU LISTEN TO AT THIS TIME?

I'm a Oscar Peterson-fantast. Yeah! Oscar Peterson, Errol Garner, and Pete Johnson. Pete Johnson was my first favorite. It was late 1930's and 1940's. I used to play a Pete Johnson song, called "627 Stomp". That was my signature then.

HOW DID YOU TO GET IN CONTACT WITH CHUCK BERRY?

I heard him at a club in East St. Louis called Hoff's Garden. I liked the way he played the guitar. One evening when I was playing, my saxophonist became ill. I called Chuck and asked if he could have the possibility to play the guitar. And he said, "sure, I can play". He came home to me and we played through the songs and then we drove to the show.

Chuck Berry in concert, Norrvikens TrÀdgÄrdar, BÄstad, Sweden, July 5, 1987

Photo: Johan Hasselberg

WHO PLAYED THE SAXOPHONE IN THE JOHNNIE JOHNSON TRIO?

His name was Alvin Bennett. But it was only until 1954. Now he is paralyzed. He can't even... yes, you know.

WAS IT A BASS PLAYER IN THE BAND?

No, it was drums, piano, and saxophone, and then guitar when Chuck came along. We played most at Club Cosmopolitan in East St. Louis. Ebbie Hardy, who played drums, suffered a heart attack and died a few years ago (1983).

CHANGED THE BAND NAME WHEN CHUCK CAME?

No, it was still called The Johnnie Johnson Trio. It was only when Chuck went to Chicago and met Leonard Chess we renamed the band. We recorded the single "Maybellene" and Chuck said, "Johnnie, is it okay that I call it The Chuck Berry Combo?". I said, "Of course, you paid the gas to Chicago", and then it became The Chuck Berry Combo.

Left to right: Chuck Berry, George French, Johnnie Johnson in concert, Norrvikens TrÀdgÄrdar, BÄstad, Sweden, July 5, 1987

Photo: Bo Berglind

YOU PLAY A MELODY ON THE PIANO ON MANY OF CHUCK BERRY'S SONGS.

That's what Chuck Berry wanted me to play. I play as I feel so everything rolls smoothly, just like ice cream on a cream cake!

IT WORKS AS A SOLO INSTRUMENT.

That's right and that's what Chuck Berry likes with my pianoplaying. That's why he doesn't like someone else's pianoplaying than mine! Let me give a good example. Chuck and I have recorded some songs that have not been released. For example, Frog's "Good Times Boogie" and "Honky Tonk Train". It was in the 1950's. It was my music style, but Chuck and I could play together and it sounded like Chuck Berry's music. Chuck is still playing some jazz, as for example, "Jazz at the Philharmonic". He plays all kinds of music!

DO YOU STILL PLAY IN THE CLUBS IN ST. LOUIS?

Yes, three nights a week.

DO YOU PLAY ALONE OR DO YOU HAVE A BAND?

I have a band called Johnnie Johnson & The Magnificent Four, and when Chuck comes to town he plays with us.

WHAT REPERTOIRE DO YOU HAVE?

There are blues, jazz, rhythm & blues, and usually rock when Chuck visit us.

DO YOU EVEN SING?

No, no, I can always talk, but do not sing!

YOU HAVE BEEN AWARDED A DISTINCTION AT ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME.

Yes, I was chosen as the fourth biggest rock'n'roll pianist throughout the ages. It was Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and myself. I didn't know about it, but they sent me a magazine afterwards.

THANK YOU, JOHNNIE !!

Thank you, I hope to see you again!

And, Johan tells, they met again: "Johnnie gave me his address and two years later I greeted him in St. Louis, and listened to Johnnie Johnson & The Magnificent Four."

Many thanks to Morten and Johan for sharing these memories with us!

Monday, June 27. 2022

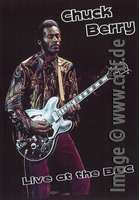

Chuck Berry - Live from Blueberry Hill - explained

Around Christmas 2021 Dualtone Music released a "new" Chuck Berry album containing live recordings from 2005 and 2006.

Since 1996 Berry had played regular shows at Joe Edwards "Blueberry Hill" in St. Louis, more than 200 of them. In contrast to the huge concert halls typically used for Berry concerts, the 300-seat "Duck Room" brought back the club atmosphere from the 1950 when Berry started to perform in St. Louis.

Also in contrast to his other concerts world-wide, the Blueberry Hill shows always had the same line-up for almost twenty years. The "Blueberry Hill Band" consisted of Berry's children Charles, Jr. and Ingrid, his band leader and bass player for 40+ years Jim Marsala, plus Robert Lohr on piano and Keith Robinson on drums.

As we already know from Dualtone Music, "Live from Blueberry Hill" is sold in many different ways: on CD, as a digital download, and in various Vinyl variants. The music is always the same, and this is what this site is about.

The liner notes to the CD tell a bit about the shows, but very little about the music. There's not even a recording date given, just "All songs recorded live at Blueberry Hill, St. Louis, MO from July 2005 - January 2006". I therefore contacted Bob Lohr, who played piano on all tracks, to find out more about how the recordings were created. Here's what I learned.

Bob Lohr (to the right) and the band (Jim Marsala, Charles, Ingrid, and Chuck Berry) live at the Blueberry Hill 2009

photos courtesy of Doug Spaur, many thanks, Doug! Click to enlarge.

Bob, do you remember when you started playing with Chuck at the Blueberry Hill or at other venues?

Please tell our readers a bit about your musical work. How often did you perform with Chuck, with whom did you share stages?

Thinking back at the Blueberry Hill shows, what made them special in comparison to playing at large halls?

The new CD presents a short show of just 30 minutes. Was this the standard length of the Blueberry Hill performances?

30 minutes seem to become the new standard for albums. Given that many people listen to music using digital streaming, 30 minutes seems to be "long enough" for the labels and for the listener's attention span.

As for the song selection, we only hear Chuck's greatest hits plus Walter Jacobs' "Mean Old World". Was this a typical tracklist?

Do you remember Chuck playing more obscure and rare songs from his huge repertoire? On the CHUCK album for instance there's a Blueberry Hill recording of Tony White's "Enchiladas".

What do you think is missing from new CD? Is there any special song you remember from Blueberry Hill which you wished to hear again?

Ingrid is heard only on two tracks, "Mean Old Word" and "Let It Rock". Was it typical that she only joined small segments of the show? Or has she been with you only sometimes and was absent when the other tracks were recorded?

The two songs Ingrid plays harmonica on as well as "Roll Over Beethoven" are also the only three songs on this album we hear you soloing. Have you been allowed to solo during the shows? Or was it just Chuck and the rhythm he needed?

A reviewer wrote that to his ears Charles Jr. is playing the lead of "Johnny B. Goode" on the new CD. Did father and son share and distribute the lead guitar solos?

Chuck was close to eighty years when these recordings were made. We almost cannot notice when he sings and plays.

Bob, what is your favorite recollection from Blueberry Hill?

Many thanks for your explanations, Bob! We appreciate to hear from "the sources".

Since 1996 Berry had played regular shows at Joe Edwards "Blueberry Hill" in St. Louis, more than 200 of them. In contrast to the huge concert halls typically used for Berry concerts, the 300-seat "Duck Room" brought back the club atmosphere from the 1950 when Berry started to perform in St. Louis.

Also in contrast to his other concerts world-wide, the Blueberry Hill shows always had the same line-up for almost twenty years. The "Blueberry Hill Band" consisted of Berry's children Charles, Jr. and Ingrid, his band leader and bass player for 40+ years Jim Marsala, plus Robert Lohr on piano and Keith Robinson on drums.

As we already know from Dualtone Music, "Live from Blueberry Hill" is sold in many different ways: on CD, as a digital download, and in various Vinyl variants. The music is always the same, and this is what this site is about.

The liner notes to the CD tell a bit about the shows, but very little about the music. There's not even a recording date given, just "All songs recorded live at Blueberry Hill, St. Louis, MO from July 2005 - January 2006". I therefore contacted Bob Lohr, who played piano on all tracks, to find out more about how the recordings were created. Here's what I learned.

Bob Lohr (to the right) and the band (Jim Marsala, Charles, Ingrid, and Chuck Berry) live at the Blueberry Hill 2009

photos courtesy of Doug Spaur, many thanks, Doug! Click to enlarge.

Bob, do you remember when you started playing with Chuck at the Blueberry Hill or at other venues?

1996âŠon Chuckâs 70th birthday. The first three shows were in a different club room at Blueberry Hill called the Elvis RoomâŠcould probably fit 100 people maximumâŠabout the size of a basement recreation room w/ Elvis memorabilia in glass cases on the walls. Joe Edwards later built the Duck Room in 1997 after he took over an adjoining restaurant (Ciceroâs) which moved up the street. Ciceroâs had a music club in the basement which was very smallâŠhad a lot of local acts plus well known national acts occasionally (I played there in local blues bandsâŠalso saw the Doorsâ Ray Manzarek live w/ poet Michael McClure once!). Joe Edwards expanded Ciceroâs club space, including digging out the floor a couple of feet deeperâŠand the Duck Room was born!

Please tell our readers a bit about your musical work. How often did you perform with Chuck, with whom did you share stages?

With Chuck I played almost all the shows at Blueberry Hill (over 200) and at least 100 on the road/private gigs/local gigs outside of Blueberry HillâŠan estimate would be some 350 shows in total.

Onstage, Iâve gigged w/ Willie âBig Eyesâ Smith & Calvin âFuzzâ Jones (Muddy Waters rhythm section), Billy Boy Arnold, Jimmy Rogers, Sam Lay, Roy Gaines, Snooky Pryor, Hubert Sumlin, Albert Collins, Big Jack Johnson, Sam Carr, Mud Morganfield, Cyril Nevilleâs Royal Southern Brotherhood & many others. Lots of well-known blues artists over the years.

Hereâs a partial discography on me: https://www.allmusic.com/artist/bob-lohr-mn0000057405

Thinking back at the Blueberry Hill shows, what made them special in comparison to playing at large halls?

It was a 300-seat venue which made it a more intimate experience for the fansâŠthe St. Louis version of Liverpoolâs Cavern Club. Chuck always had a lot of interaction with audiences wherever he playedâŠcheck out various YouTube clips. People flew in from all over the world to see Chuck at Blueberry Hill. After tickets became obtainable online, people would come up to me after the show from all over the world. Oftentimes I would take them to downtown St. Louis to either BBâs Jazz Blues & Soups or Beale on Broadway to hear some serious blues/r&b. A lot of these tourists were traveling through what I call âBlues/Rock Ground Zeroâ, or hitting all the music cities within a 300-mile radius of St. Louis: Chicago, Memphis/Clarksdale, Nashville etcâŠ

The new CD presents a short show of just 30 minutes. Was this the standard length of the Blueberry Hill performances?

No, Chuckâs standard show was 1 hour wherever we played.

30 minutes seem to become the new standard for albums. Given that many people listen to music using digital streaming, 30 minutes seems to be "long enough" for the labels and for the listener's attention span.

As for the song selection, we only hear Chuck's greatest hits plus Walter Jacobs' "Mean Old World". Was this a typical tracklist?

No, we did at least two or three blues numbers per gig. âWee Wee Hoursâ of courseâŠalso âIt Hurts Me Tooâ and âKey To The Highwayâ, âEvery Day I Have The Bluesâ, âWorried Life Bluesâ, âBeer Drinkinâ Womanâ etc.

Do you remember Chuck playing more obscure and rare songs from his huge repertoire? On the CHUCK album for instance there's a Blueberry Hill recording of Tony White's "Enchiladas".

Not reallyâŠwould usually play the well known songs.

What do you think is missing from new CD? Is there any special song you remember from Blueberry Hill which you wished to hear again?

We used to do âBrown Eyed Handsome Manâ and âPromised Landâ on an occasional basisâŠalso, âWorried Life BluesââŠ

Ingrid is heard only on two tracks, "Mean Old Word" and "Let It Rock". Was it typical that she only joined small segments of the show? Or has she been with you only sometimes and was absent when the other tracks were recorded?

She was at every show in St. Louis onstage. She did not go on every road trip.

The two songs Ingrid plays harmonica on as well as "Roll Over Beethoven" are also the only three songs on this album we hear you soloing. Have you been allowed to solo during the shows? Or was it just Chuck and the rhythm he needed?

As you can hear on the latest live CD, Chuck would throw us solos on almost every songâŠvery generous in that regard.

A reviewer wrote that to his ears Charles Jr. is playing the lead of "Johnny B. Goode" on the new CD. Did father and son share and distribute the lead guitar solos?

No, thatâs clearly Chuck on Johnny B. Goode here. Chuck did almost all the lead guitar on stage and threw Charles Jr. some solos during the set. Charles Jr. does a solo at approximately 1:57 of Roll Over Beethoven right after mine. Charles Jr.âs rhythm guitar can be heard throughout this CD on the left channel.

Chuck was close to eighty years when these recordings were made. We almost cannot notice when he sings and plays.

You cannot notice in these 2005 shows, but as his later show recordings sadly indicated, Chuckâs hearing was seriously degraded. He had some expensive hearing aids but he didnât like wearing them onstageâŠone actually fell out on the stage and could not be found later!

Bob, what is your favorite recollection from Blueberry Hill?

One of the coolest things I remember about the Blueberry Hill shows was hearing and watching Chuck warm up with his guitar backstage before the show. Chuck would warm up with his guitar while not plugged into an amplifier. It was amazing to hearâŠall the classic Chuck Berry licks played perfectly by the man himselfâŠoften did some amazing things which I never heard him do onstage. It was like all the years and age were stripped away and he was back again playing in the 50âsâŠIâm so sorry that I never asked Chuck whether he would allow me to record him on my iPhoneâŠabsolutely amazing. You could also hear him warming up when he was changing clothes in the bathroom. Once he opened the door and I watched him playing guitar in the mirrorâŠChuck told me he liked playing in the bathroom because the reverb reminded him of the Chess studio!

Many thanks for your explanations, Bob! We appreciate to hear from "the sources".

Saturday, May 7. 2022

Run! Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer â and the copyright mystery

It's Christmas time and while listening to the radio, from time to time you'll hear one of the various cover versions of Berry's Run Rudolph Run. Berry's???

While everyone will tell you that this is a typical Chuck Berry song with a typical Berry melody (later re-used at the same session for Little Queenie) and typical Berry lyrics (Said Santa to a boy child, "What have you been longing for?" — "All I want for Christmas is a Rock and Roll electric guitar!"), all over the Internet you will read that this song was written by Johnny Marks and Marvin Broadie! And this includes Wikipedia âŠ

With the help of three fellow Berry experts, biographer Bruce Pegg, discographer Morten Reff, and sessionographer Fred Rothwell, I've tried to sort out a few facts from the rumors.

In 1939 Robert L. May wrote the story of Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer, first for his daughter Barbara, later as a giveaway booklet for his employer, the Montgomery Ward Company. Ward's was the first owner of the Rudolph copyright. In 1946 the copyright was transferred back to May and today belongs to The Rudolph Company, L.P., that means May's heirs.

In 1949 Johnny Marks, husband of May's sister Margaret and both a songwriter and radio producer, took the tale and created the famous Christmas song Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer. The singing cowboy Gene Autry seems to be the first who recorded the song (though some sources name Harry Brannon) and made it a huge hit. Copyright to the 1949 Rudolph song is owned by Marks own publishing company called St. Nicholas Music, Inc.

In 1958, Chuck Berry recorded his version of a Christmas story named Run Rudolph Run. The original Chess release 1714 came with this authors line:

(C. Berry Music — M. Brodie) / ARC BMI

Chuck Berry Music, Inc., Berry's company, is listed here as the author as it is on most Chess singles starting with Beautiful Delilah up to Ramona Say Yes. For some reasons, probably financial, it seems to have made sense to use a company name here instead of an individual's name. As the melody is pure Chuck Berry, it's no wonder that Chuck Berry Music, Inc. claimed authorship and that ARC, the Chess/Goodman publishing company, claimed copyright.

But, mystery #1:

Who is "M. Brodie"? Chuck Berry using a co-writer? A person named M. Brodie does not exist on the Internet. Not as a songwriter nor in any relation to a record company. So if M. Brodie was a songwriter, Run Rudolph Run is his or her only published work. But M. Brodie might also have been someone Berry or the Chess Brothers wanted to give a favor (money/fame) â as they did with Alan Freed on the original Maybellene record. Or M. Brodie might be just a pen name such as "E. Anderson" on Let It Rock who was Berry in disguise.

In the ASCAP authors database, the co-writer of Run Rudolph Run named M. Brodie is identified as member number 268788988. While it's strange that Run Rudolph Run even exists in the ASCAP database because the original single clearly refers to the rival songwriter organization BMI, it becomes even more strange:

Member number 268788988 has additional entries for songs he wrote or co-wrote. All these additional songs stem from albums recorded by a late 1990s group called the Soultans of which a Marvin Lee Broadie was lead singer. And Marvin Lee Broadie indeed wrote some Soultans songs such as Cross My Heart on their Love, Sweat and Tears album. But if you look at Broadie's photo on his concert management site, I strongly doubt he was even born when Berry's Rudolph hit the record stores. Or, as Bruce Pegg puts it:

So unless this songwriter wrote one song in 1958, then had 40 years of writers block only to surface again as a writer for a German pop band at the end of the 90s, this Mr. Broadie is not our man.And don't overlook the different spelling of M. Brodie and Marvin Broadie.

So let's go to mystery #2:

Up to today on all Chess records or re-releases Berry's recording is always credited to Berry/Brodie or just Berry, this includes the latest HIP-O-Select boxes. In contrast, the ASCAP database and almost all cover versions name the songwriters as Johnny Marks and Marvin Broadie. Marvin Broadie aside, what has Johnny Marks to do with the Berry song?

Wikipedia claims that Marks indeed wrote the song, though Wikipedia fails to give a source for this claim. Is it likely that Marks wrote the Berry tune? Not if you compare Run Rudolph Run to Autry's hit record. But if you knew that in 1958 Marks wrote Brenda Lee's Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree, that story might not be too far away. Our mysterious M. Brodie could be an alias for Johnny Marks, which allowed him (an ASCAP songwriter) to team up with Berry (a BMI songwriter). However, while this is possible, I don't believe it.

More likely is a different, more logical link to Marks. His publishing company St. Nicholas Music, Inc. is very strict about copyrights. And in fact the company was created by Marks just because of the Rudolph song and to cash on its success. As such it has "exploited the name and likeness of Rudolph via trademarks in connection with a wide variety of products and services, such as musical performances, audio recordings, sheet music and other music publications" (quoted from court papers). So Marks may have forced Arc Music/Chess Records to register the song with ASCAP and under the Marks/Brodie name. St. Nicholas Music, Inc. along with Character Arts, LLC (which owns the rights to the Rudolph 1964 TV special) successfully forbids Rudolph to appear in movies unless you pay for a license. And they certainly forbid Rudolph to appear in songs as well.

I'm really glad that my rights to the Rudolph name are older than theirs. Otherwise I might have feared their lawyers for using it.

The mysteries remain. I am 100 per cent sure that the mysterious M. Brodie never heard himself called Marvin. This dual use of the 268788988 member number in the ASCAP database is certainly an error introduced by trying to remove variant spellings for the same writer. This is where M. Brodie was mixed up with Marvin Lee Broadie. Johnny Marks' entry to the game was most certainly due to legal reasons. I strongly doubt Marks' contribution to the song, but if you can put some light into this darkness, let me know.

[Addition 31-01-2022:]

Someone sent me a copy of a Facebook post by Daryl Davis, who played piano behind Chuck Berry in later years. Unfortunately I don't have a link or date to share.

Daryl reports on a discussion between him and Berry in preparation for a New Year's Eve show at B.B.King's in NYC:

I asked him about why Run Run Rudolph a/k/a Run Rudolph Run was often credited to Johnny Marks and somebody named Brodie. He said that he wrote the song himself but the name "Rudolph" had been trademarked and the publishing company publishing his songs had been sued for his using it. He was perturbed that the publishing company didn't fight the suit more vigorously, because Johnny Marks had nothing to do with his song and now he had to share the copyright. He also said that Brodie did not exist and it was a scheme to make more money for Marks and his publisher. He regretted not pursing it more at the time. But he still continued to make a lot of money from the song, just not as much as he was entitled to make. It was a bittersweet song for him.

[Addition 07-05-2022:]

In today's news there was some reporting about limitations to fair use of fictional characters in local copyright laws, in this case German Urheberrecht. A very well-known song in Europe is the title song to the 1969 TV series Pippi Longstocking. The original Swedish lyrics were written by Astrid Lindgren herself (melody by Jan Johansson). The German lyrics were written by Wolfgang Franke. 60 years after Lindgren's initial complaints about not getting compensation for use of her fictional character in Franke's text, copyright court rulings and a final settlement between the heirs explained that at least following these local laws you're not free to use the name and properties of a fictional character without sharing the income. Following this, at least here in Germany Robert May was entitled to shared copyright on the Rudolph lyrics.

Friday, April 16. 2021

The Toronto Concert Complete - not yet - still

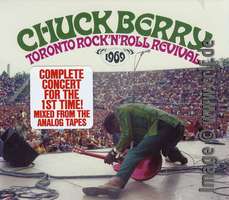

Everyone interested in Chuck Berry's music knows the Toronto concert. This is because Berry's performance at the Toronto Rock&Roll Revival festival of September 13th, 1969 has been recorded professionally both on film and on audio tape.

The audio was published on hundreds of vinyl and CD albums starting with the 2-LP set Live in Concert (Magnum LP-703) in 1978. The optical recording was used as early as 1970, most importantly in D.A. Pennebaker's movie Keep On Rockin' from 1972.

The interesting thing to collectors is that none of the audio or video releases contains the entire performance. The 2-LP set has, very uncommon for a live recording, each song completely separated with faded start and ending. The movie contains just a selection of songs as well as some in-between talks, but cut and spliced as it fitted to the director.

it is totally unclear why there has never been a complete release of the entire show. At least in the 1980s and 1990s a more complete source still existed, as budget re-releases of the concert contained indeed MORE than the original Magnum album. For instance a French LP album contains half a minute of introduction between School Day and Wee Wee Hours.

Thus at least in the 1990s some company still owned a more complete, maybe entire tape of the show they could license. Some labels used this, though never in total.

It is unclear whether this tape still exists somewhere. When Bear Family in 2014 released their huge Berry box, they tried to find it, but didn't succeed. Therefore Bear Family extracted the only song from the show still missing an audio release (the short Bonsoir Cherie) from Pennebaker's movie.

We all thought this would be the end of the story. But a few days ago, Sunset Blvd. Records released another audio CD with music from Toronto, but promoted their release with a prominently placed large sticker:

Even those like me who already have dozens of records containing the same show, felt tempted to buy one of the (pretty expensive) CDs. Don't do it!

Also Sunset Blvd. Records (SBR) did NOT find the original audio tape. Instead they cut and spliced available and well-known material trying to recreate the original concert. There's nothing wrong trying so. I did the same in 1997. However, I used all the material from all the sources. SBR obviously only had the Magnum album and Pennebaker's film.

This means that several of the transitions between songs are missing from this CD. And it means that what sounds like on-stage chatter and comments is not at the correct place, since Pennebaker already had cut and spliced segments from all over the concert and shuffled them around.

The songs are not in the correct sequence and parts of the show are omitted even though already known. The only interesting thing is that SBR included Kim Fowley's introduction to Berry.

So this is a fake! And at some time SBR must have recognized it. MC Kim Fowley is heard twice at song endings applauding Berry. One is at the non-medley version of Johnny B. Goode and thus also on the SBR CD. A second time is at the end of Maybellene.This and its placement at the end of the Magnum 2-LP set lets me assume that this song is one of the rare encores in a Berry concert. SBR instead decided to place Maybellene after I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man which ends with Berry asking "You name it, we play it." Maybellene starts with "Did I hear Maybellene?" Fits, thought the people at SBR. But this required them to cut off Kim Fowley from the end of the song and to fade over into Too Much Monkey Business.

And indeed it's too much monkey business here. Why to spend all the effort to create such a fake? Either you have the original tape or you don't. But don't pretend to have it.

Interestingly the liner notes refer to and correctly name our database as a source. So they must have found this site. But why didn't they read the long chapter we have dedicated to this concert alone? All this leaves us fairly disappointed.

To end with a positive note: Have a look at Don Pennebaker's description about how the title Keep On Rockin' got selected and about his visit to John Lennon's bedroom showing him the film: https://phfilms.com/films/sweet-toronto-keep-on-rockin/#summary

Somehow Pennebaker misses to tell that Lennon demanded payment for his appearance and thus had to be cut from the film.

The audio was published on hundreds of vinyl and CD albums starting with the 2-LP set Live in Concert (Magnum LP-703) in 1978. The optical recording was used as early as 1970, most importantly in D.A. Pennebaker's movie Keep On Rockin' from 1972.

The interesting thing to collectors is that none of the audio or video releases contains the entire performance. The 2-LP set has, very uncommon for a live recording, each song completely separated with faded start and ending. The movie contains just a selection of songs as well as some in-between talks, but cut and spliced as it fitted to the director.

it is totally unclear why there has never been a complete release of the entire show. At least in the 1980s and 1990s a more complete source still existed, as budget re-releases of the concert contained indeed MORE than the original Magnum album. For instance a French LP album contains half a minute of introduction between School Day and Wee Wee Hours.

Thus at least in the 1990s some company still owned a more complete, maybe entire tape of the show they could license. Some labels used this, though never in total.

It is unclear whether this tape still exists somewhere. When Bear Family in 2014 released their huge Berry box, they tried to find it, but didn't succeed. Therefore Bear Family extracted the only song from the show still missing an audio release (the short Bonsoir Cherie) from Pennebaker's movie.

We all thought this would be the end of the story. But a few days ago, Sunset Blvd. Records released another audio CD with music from Toronto, but promoted their release with a prominently placed large sticker:

Even those like me who already have dozens of records containing the same show, felt tempted to buy one of the (pretty expensive) CDs. Don't do it!

Also Sunset Blvd. Records (SBR) did NOT find the original audio tape. Instead they cut and spliced available and well-known material trying to recreate the original concert. There's nothing wrong trying so. I did the same in 1997. However, I used all the material from all the sources. SBR obviously only had the Magnum album and Pennebaker's film.

This means that several of the transitions between songs are missing from this CD. And it means that what sounds like on-stage chatter and comments is not at the correct place, since Pennebaker already had cut and spliced segments from all over the concert and shuffled them around.

The songs are not in the correct sequence and parts of the show are omitted even though already known. The only interesting thing is that SBR included Kim Fowley's introduction to Berry.

So this is a fake! And at some time SBR must have recognized it. MC Kim Fowley is heard twice at song endings applauding Berry. One is at the non-medley version of Johnny B. Goode and thus also on the SBR CD. A second time is at the end of Maybellene.This and its placement at the end of the Magnum 2-LP set lets me assume that this song is one of the rare encores in a Berry concert. SBR instead decided to place Maybellene after I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man which ends with Berry asking "You name it, we play it." Maybellene starts with "Did I hear Maybellene?" Fits, thought the people at SBR. But this required them to cut off Kim Fowley from the end of the song and to fade over into Too Much Monkey Business.

And indeed it's too much monkey business here. Why to spend all the effort to create such a fake? Either you have the original tape or you don't. But don't pretend to have it.

Interestingly the liner notes refer to and correctly name our database as a source. So they must have found this site. But why didn't they read the long chapter we have dedicated to this concert alone? All this leaves us fairly disappointed.

To end with a positive note: Have a look at Don Pennebaker's description about how the title Keep On Rockin' got selected and about his visit to John Lennon's bedroom showing him the film: https://phfilms.com/films/sweet-toronto-keep-on-rockin/#summary

Somehow Pennebaker misses to tell that Lennon demanded payment for his appearance and thus had to be cut from the film.

Friday, October 18. 2019

Chuck Berry in Stereo

When Jack Wiener in 1957 built the famous Sheldon Recording Studios at 2120 South Michigan Av. in Chicago where Berry's most important recordings were made, he had provisions to record in Stereo. However, this “double-mono” system was not intended to create stereo recordings but instead mainly thought of as a secondary backup mono system in case some gear failed.

We do not know if any of Berry's early Chess recordings were recorded in Stereo. What we do know is that at least in February 1960 Stereo finally made it to the recording process. This is because “Diploma For Two”, recorded Feb. 15th, 1960, is available as a true stereo version which was released in 1967 on a British album (“You Never Can Tell”, Marble Arch MALS-702).

As Remastering and Restoration Engineer Steve Hoffman tells, the Chess studios got a four-track recording machine in 1959. They now started to record everything in both Mono and Stereo concurrently. It was common then to do a dedicated mono mix on one of the four tracks with the other three tracks used by three stereo channels (left, center, right). [https://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/chuck-berry-rock-n-roll-rarities-and-more-rock-n-roll-rarities-info.854690/]

However, Andy McKaie (who for instance created the Berry 4-CD sets on Hip-O Select and won the Grammy award “Best Historical Album” for the 1988 “Chuck Berry — The Chess Box”) is quoted saying,

As far as mono versus stereo goes, it seems that if they recorded something specifically for an album in the '60s it was recorded and mixed in stereo. If recorded for a single, it's a toss-up, and for extended periods of time, they never bothered to do anything but mono mixes. [Some specific non-Berry] '63 sessions [...] were recorded and assembled for an album, but only a mono assembly was done and the multi-tracks are either unmarked in our vault or missing. The running masters from those sessions are even only in mono, whereas I have found running masters from 1959 Howlin' Wolf that are in stereo. Then again, nothing but mono exists from Wolf's Red Rooster in '61, though there's a stereo master for Shake for Me from same session. The inconsistency drives me nuts, too, but I can only issue what we have available to me to issue. Sometimes life is like that. — Chess used to keep a two track running for sessions, even when they were doing multi-track sessions. Sometimes the two track seemed to be in mono, sometimes stereo. Before he died, Ron Malo told me that Chess really didn't care about or understand stereo, so if an engineer or a producer didn't dwell on it, what you got was a tossup. Leonard did the Muddy sessions, except for the concept albums, and according to Ron, he really wasn't interested in stereo - his notion was that he was making a single to sell... [https://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/for-steve-stereo-remixes.1192/page-2]