Monday, June 20. 2016

Chuck Berry live in New York 1956

Anthony Chanu asked me:

Did you notice that the live version of Roll Over Beethoven on the first HIP-O-Select set is different from the version used on the early Radiola album?

No, I didn't. But it reminded me that I always wanted to write something about this recording and its releases. Time to do so.

Live recordings of early performances of the 1950's Rock'n'Rollers are extremely rare. Even though the artists played hundreds of gig each year, no audience tapes or concert recordings were made. In contrast to the 1970s and onwards, where visitors recorded and saved almost every concert, in the 1950s there was no portable personal audio recording equipment available. Even record companies had no intention to tape the raw public performance instead of using a clean and controlled studio environment. Too much effort, too bad quality.

Due to this, the only surviving performance recordings from the 1950s stem from radio and TV broadcast as well as from movies. Movies and TV broadcast however usually had the artists lip-syncing to a playback of their hit records meaning these are not live performances even if some audience is heard.

The only surviving true live performances by Chuck Berry recorded in the 1950s are from the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958 and from New York, 1956. The Newport recordings were made because some of it was used for the movie "Jazz on a Summer's Day". The story behind the New York recordings is even more interesting:

Between March 24 and September 25, 1956, Alan Freed hosted a series of 26 shows on CBS radio. Each show ran half an hour and was called âThe Camel Rock'n'Roll Dance Partyâ. Most of the shows were recorded in New York and produced by WCBS, CBS' New York radio station. The shows from May to mid-June were recorded in Hollywood and produced by KCBS instead because Alan Freed was filming in Hollywood then.

Chuck Berry, who was in New York for filming his segment of Alan Freed's "Rock, Rock, Rock" movie, contributed to the twenty-second show which was broadcast on Tuesday, August 28, 1956. Along with him were The Flamingos and Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers. It is not clear when and where the show was recorded. It may have been broadcast âliveâ as most other 1950s radio shows were. Since there is a loud audience to be heard, the venue must have been a smaller theater. Most likely it was CBS-TV Studio 50, now the Ed Sullivan Theater, on Broadway or the theater in CBS' Studio Building at 52nd Street.

Many of the original tapes from the Camel Rock'n'Roll Dance Party as used for broadcast have been made available to the public in 2015. You can listen to them at archive.org.

In addition the AFRTS (United States Armed Forces Radio and Television Service) created transcription records from the broadcasts. These transcription records were then sent out to AFN radio stations worldwide for broadcast to US military in foreign countries. (This image shows a sample AFRTS record label. If you have a label scan of this or any other Rock'n'Roll Dance Party transcription, please email it to the address given under Copyright to the right.)

The AFRTS transcriptions were edited over the original broadcast. Most importantly all the advertising spots and the name of the show sponsor "Camel Cigarettes" were removed from the recording. This cut off almost five minutes from each show. In addition AFRTS added a different out cue to the show. The transcription records containing the edited shows were produced in small quantities for the AFN stations abroad. A few of them survived until the 1970s, even though their unusual format of 16-inch diameter required special turntables to play.

The AFRTS versions of most of the shows are available from the Old Time Radio Catalog as Audio-CDs.

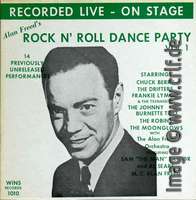

Snippets of these shows taken from the AFRTS disks have found their way to commercial albums and CDs since the 1970s. The first record I know of was Radiola's Rock'n'Roll Radio (Radiola MR-1087) published in 1978. Roughly at the same time a series of five albums called Alan Freed's Rock n' Roll Dance Party (WINS 1010-1014) came out with the same and additional segments from the AFRTS records. The Flamingos' performance of the August 28 show was to be found only on the WINS release, while both Berry and the Teenagers were on both. A CD release containing 27 tracks was published by Magnum Force in 1991 as Rock And Roll Dance Party (Magnum Force CDMF 075).

The August 28 show starts with Bern Bennett announcing Alan Freed. Freed then opens the show and introduces his house band led by Sam "The Man" Taylor which start a four-minute instrumental called Pretzel. Next follows a lengthy Camel spot introduced by Freed as "the Camel song". After the advertisement The Flamingos sing A Kiss From Your Lips and, as Freed proudly declares, their upcoming next release The Vow. After this another Camel spot explains in detail while one has to smoke only the sponsor's cigarettes.

"And now back to our Camel Rock And Roll Dance Party. And here's the guy that is just the greatest: Chuck Berry and Maybellene!" In less than two minutes Berry runs really fast through his first record. Of the band only the drummer is heard with a short solo. "Wow!" sighs Freed and directly announces the next number: "Chuck Berry and his current bagel, right back to our Camel mike with Roll Over Beethoven!" Again we hear mostly Berry playing both lead and rhythm on his guitar. During the mid-song solo, the crowd hollers and shouts "Go! Go! Go!" indicating that we probably miss seeing Berry duck-walking across the stage. At the very end of the song, one of the sax players cannot step back any longer and adds some answering licks. With "Chuck Berry, just fabulous!" Freed ends Berry's performance.

And the show returns to promoting Camel cigarettes. After that Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers perform I Promise To Remember and Why Do Fools Fall In Love followed by another spot featuring the Camel song. The show ends with Sam Taylor and the Big Band going crazy on another instrumental called Look Out! Alan Freed once again praises Camel and finishes the show.

As said, the AFRTS edits of the show exclude all the Camel spots as well as all mentions of the sponsor in Freed's announcements. So here it goes "right back to our (cut) mike with Roll Over Beethoven." Maybellene is about 2:00 minutes long and Roll Over Beethoven clocks at 3:10 approximately.

But on HIP-O Select's release of the 4-CD set Johnny B. Goode - His Complete '50s Chess Recordings (HIP-O-Select B0009473-02, 2008) this song only runs for 2:44 minutes. And if you listen closely, you will notice that after the solo almost a complete verse is missing and replaced with a segment from the beginning of the show. Why?

I asked Fred Rothwell who helped compiling the CD sets. He told me that Andy McKaie of Universal Music had found one tape in the MCA archives containing both the two 1956 live songs and eight unusual Chess studio recordings with artificial audience dubbed. Even though the live songs we not Chess recordings they decided to include them on the set. And this edited version is as it was on the tape.

At that time no-one noticed that this was a damaged or repaired track. Fred said that he later became aware of this and when he compiled the recordings for the Bear Family boxset Rock And Roll Music - Any Old Way You Choose It (Bear Family BCD 17273 PL, 2014) the correct and complete track from the AFRTS transcription record was used.

Eight unusual Chess studio tracks with audience dubs and the two Camel show tracks on one tape? This made me remember one of the stranger LP albums I have in my collection: Alive And Rockin' (Stack-O-Hits Records AG9019, 1981).

This album had the two 1956 live tracks plus eight rarities which at that time were otherwise only known from the American Hottest Wax bootleg (Reelin' 001): previously unreleased versions of Rock And Roll Music, 21 (here called Vacation Time), Reelin' And Rockin', Sweet Little Sixteen, and Childhood Sweetheart along with the undubbed version of How High The Moon plus the previously unknown songs I've Changed (here called just Changed) and One O'Clock Jump (here as Chuck's Jam). All eight tracks were "enhanced" with fake audience on the Stack-O-Hits release. Yes: How High The Moon which was released in 1963 with audience noise and finally came to light in its original form on the Reelin' bootleg, was re-destroyed with different audience noise.

Fred confirmed that these are exactly the eight tracks from the mysterious tape in Universal's archive. And yes, the album also contains the edit of the Camel show live recording of Roll Over Beethoven. So this is not new, we only never recognized it.

Does this mean that Chess had created another fake live album and released it on the Stack-O-Hits label? Certainly not. In 1981 the Chess archives were owned by All Platinum Records and all they did with it was a hit sampler called The Great Twenty-Eight.

So who was Stack-O-Hits Records? Probably no-one at all. Stack-O-Hits was one of a dozen names used by a company called "Album Globe Distribution" (hence the AG catalog number). A.G. was known "notorious for its quasi-legitimate and downright illegal releases. Every record they issued used a different label name, but all have an AG prefix followed by a 4-digit number". (quote from discogs.com)

While the album's liner notes praise Berry to have "directly and primarily influenced artists from The Beatles, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, Rod Steward, to Bob Seger, Led Zeppelin and so many more", they completely lie about the origins of the recordings contained:

Stack-O-Hits is pleased to be able to bring you this fantastic live performance by Chuck Berry, recorded in his prime, performing not only a selection of his biggest hits, but a taste of gut bucket Chicago Blues and high-flyin' jazz as well. Don't let this get by -collectors take note- these performances are released for the first time here on Stack-O-Hits Records.

The only "first time" here was that we didn't knew the modified recordings before. The eight studio tracks were stolen from the Reelin' bootleg and edited to sound "live". The two true live recordings were taken from the Radiola or WINS release. Or more probably they might stem from a broken tape copy of the AFRTS transcription record as this would explain why Roll Over Beethoven was edited (repaired?).

How the master tape of Alive And Rockin' came into the MCA archives for Andy McKaie to find it there, stays a mystery. Does anybody know whether other Album Globe bootlegs were re-released by MCA or Universal?

Thanks to Fred Rothwell for help with this article!

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in Chuck Berry Live Tapes

at

13:38

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Saturday, March 5. 2016

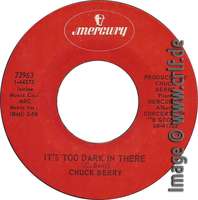

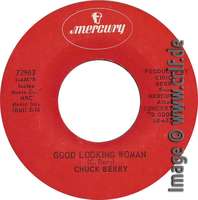

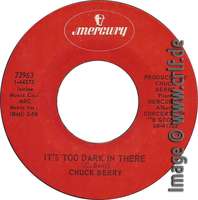

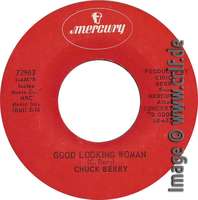

Was Mercury 72963 a regular release? Update

In November 2013 we finally gave up. For decades Morten Reff and I had tried to find a regular copy of Berry's fifth single for Mercury It's Too Dark In There / Good Lookin' Woman (Mercury 72963). While you can buy white-label promotional (WLP) copies of this single easily, we never even saw a regular copy with the commercial Mercury label.

The regular red Mercury label. This one:

Yes, it exists! Who else but reader (or shall I say contributor) Thierry Chanu found this absolute rarity!

This is the only copy of Mercury 72963 having a regular company label we know of. It came to him in the paper sleeve of the promotional copies, Thierry remembers.

So this still does not answer the question whether It's Too Dark In There / Good Lookin' Woman was ever sold in stores. It still may be that even this copy was sent out by Mercury as a promotional item. Until I see other red label copies offered in used-record shops or on the Net, I continue saying that this single was announced only but never sold. Convince me ...

The regular red Mercury label. This one:

Yes, it exists! Who else but reader (or shall I say contributor) Thierry Chanu found this absolute rarity!

This is the only copy of Mercury 72963 having a regular company label we know of. It came to him in the paper sleeve of the promotional copies, Thierry remembers.

So this still does not answer the question whether It's Too Dark In There / Good Lookin' Woman was ever sold in stores. It still may be that even this copy was sent out by Mercury as a promotional item. Until I see other red label copies offered in used-record shops or on the Net, I continue saying that this single was announced only but never sold. Convince me ...

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in Chuck Berry Rarities

at

17:46

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Saturday, February 20. 2016

Sheik of Chicago - new CD presents unreleased Chuck Berry material

The year 2016 starts with a new CD containing Chuck Berry recordings previously not released. Well, some. Well, not officially released. Well, and whether this CD is an official release is also questionable. Well, at least it looks like one.

Chuck Berry - The Sheik of Chicago (Smashing Pumpkin Records PMK-1126, 2016) comes in a cheap printed cardboard sleeve which claims to be printed in the E.U.

The CD has a playing time of almost 80 minutes consisting of a complete 1988 concert, segments from a 1981 concert, three nice short spots, and a tribute song to Chuck Berry by Joe Stampley.

The 1988 concert was recorded on New Year's Evening at the Palladium Theater in New York City. This concert had been broadcast through various U.S. radio stations and therefore this is a high-quality professional recording. The recording has been known from both audience tapes and more-or-less privately made bootleg CDs for a long time. One of these called Live at the Palladium even uses the same cover image.

While it's a high-quality recording, the performance is everything but high-quality. As he did for most of his career, Berry again uses a band he obviously has never seen before. Bass and rhythm guitar are inaudible, piano and drums are just bad. Chuck's daughter Ingrid helps out with harmonica and second vocal on a few numbers. She even gets to sing lead vocal on two blues numbers like we know from other concert recordings. All in all this concert is certainly not something you want to buy this CD for.

Following the 1988 concert are segments from a 1981 concert recorded in Reseda, California. This is much better but only 12 minutes long. Berry collectors and readers of this site know this performance for a long time. It has never been officially released for public sale. But it exists on Vinyl. These three songs have been included on a LP record sent by Westwood One to radio stations nation-wide to be broadcast as part of their In Concert radio series. Here it has been mastered digitally very well without any crackles and it's nice to have on CD now.

The first part of the former paragraph also holds for the next track. Berry's 20-seconds radio spot for the YMCA as recorded in 1967 was available on Vinyl before and has been discussed in detail on this site's section on Radio Station and Promotional Records. Here however, the transfer to CD did not go well. There are crackles, the beginning is fuzzy, and the overall sound quality is bad. However, as this recording is very rare we must be glad to be able to listen to it at all.

Jumping from 1988 to 1981 to 1967 next are two Chuck Berry recordings made in 2004. Both are speech recordings Chuck Berry did for Independence Air. The airline company Independence Air started flying in 2004 and filed bankruptcy in 2005, thus not being too successful. Besides trying to be cheap (always not a good idea) they also tried to be funny. This included that the in-flight safety announcements were spoken by comedians and other celebrities (see this old press-release).

Chuck Berry's safety announcements, to be used on their Bombardier CRJ200 (CL-65) jets, are spoken over a rock'n'roll instrumental (non-Berry). In 2004 you could download all the safety announcements from the flyi.com website. If you didn't, you now find it here on this new CD.

In addition the Pumpkin CD also includes a 30-seconds radio (?) commercial for Independence Air. In fact this is the only recording from this CD I did not know of and had before. I have not been able to find out where this spot was used and how it was distributed in 2004.

The last and 22nd track of this new CD is not a Chuck Berry recording at all. This is the song Sheik of Chicago, released in 1976 by Joe Stampley on EPIC. This Berry tribute is certainly one of the better ones and even made it to Billboard's Country Top 100.

If you are wondering about the nice and professional looking cover image, this has been cut from a contemporary (i.e. 1988) advert for Christian Brother's Brandy displaying Berry (click to enlarge).

Overall this is not necessary a CD we have been waiting for. It does include some rarities though. Thus if you don't have the radio station albums and the Independent Air MP3s, get yourself a copy.

Chuck Berry - The Sheik of Chicago (Smashing Pumpkin Records PMK-1126, 2016) comes in a cheap printed cardboard sleeve which claims to be printed in the E.U.

The CD has a playing time of almost 80 minutes consisting of a complete 1988 concert, segments from a 1981 concert, three nice short spots, and a tribute song to Chuck Berry by Joe Stampley.

The 1988 concert was recorded on New Year's Evening at the Palladium Theater in New York City. This concert had been broadcast through various U.S. radio stations and therefore this is a high-quality professional recording. The recording has been known from both audience tapes and more-or-less privately made bootleg CDs for a long time. One of these called Live at the Palladium even uses the same cover image.

While it's a high-quality recording, the performance is everything but high-quality. As he did for most of his career, Berry again uses a band he obviously has never seen before. Bass and rhythm guitar are inaudible, piano and drums are just bad. Chuck's daughter Ingrid helps out with harmonica and second vocal on a few numbers. She even gets to sing lead vocal on two blues numbers like we know from other concert recordings. All in all this concert is certainly not something you want to buy this CD for.

Following the 1988 concert are segments from a 1981 concert recorded in Reseda, California. This is much better but only 12 minutes long. Berry collectors and readers of this site know this performance for a long time. It has never been officially released for public sale. But it exists on Vinyl. These three songs have been included on a LP record sent by Westwood One to radio stations nation-wide to be broadcast as part of their In Concert radio series. Here it has been mastered digitally very well without any crackles and it's nice to have on CD now.

The first part of the former paragraph also holds for the next track. Berry's 20-seconds radio spot for the YMCA as recorded in 1967 was available on Vinyl before and has been discussed in detail on this site's section on Radio Station and Promotional Records. Here however, the transfer to CD did not go well. There are crackles, the beginning is fuzzy, and the overall sound quality is bad. However, as this recording is very rare we must be glad to be able to listen to it at all.

Jumping from 1988 to 1981 to 1967 next are two Chuck Berry recordings made in 2004. Both are speech recordings Chuck Berry did for Independence Air. The airline company Independence Air started flying in 2004 and filed bankruptcy in 2005, thus not being too successful. Besides trying to be cheap (always not a good idea) they also tried to be funny. This included that the in-flight safety announcements were spoken by comedians and other celebrities (see this old press-release).

Chuck Berry's safety announcements, to be used on their Bombardier CRJ200 (CL-65) jets, are spoken over a rock'n'roll instrumental (non-Berry). In 2004 you could download all the safety announcements from the flyi.com website. If you didn't, you now find it here on this new CD.

In addition the Pumpkin CD also includes a 30-seconds radio (?) commercial for Independence Air. In fact this is the only recording from this CD I did not know of and had before. I have not been able to find out where this spot was used and how it was distributed in 2004.

The last and 22nd track of this new CD is not a Chuck Berry recording at all. This is the song Sheik of Chicago, released in 1976 by Joe Stampley on EPIC. This Berry tribute is certainly one of the better ones and even made it to Billboard's Country Top 100.

If you are wondering about the nice and professional looking cover image, this has been cut from a contemporary (i.e. 1988) advert for Christian Brother's Brandy displaying Berry (click to enlarge).

Overall this is not necessary a CD we have been waiting for. It does include some rarities though. Thus if you don't have the radio station albums and the Independent Air MP3s, get yourself a copy.

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in Chuck Berry Recordings

at

13:21

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Thursday, February 18. 2016

CBID - Chess LP-1498 in silver - explained

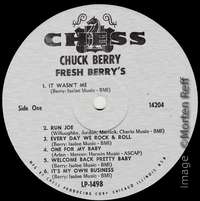

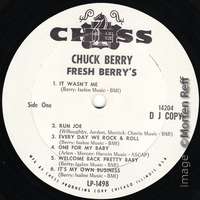

In December Morten Reff reported here about a strange copy of the Fresh Berry's album having a silver label.

He wrote:

Reader Thierry Chanu was able to explain this unusual label:

Morten agreed. When you look very closely at the label you may see the text DJ COPY stamped below the matrix number. Here is a detail of the silver label as well as the full standard white-label promo (WLP) DJ copy of this album.

When asked how he knows of only four copies of the silver label album, Thierry told me that this is from his own experience monitoring record offers for more than thirty years. He has seen this silver label copy offered only four times so far, one being Morten's.

Thanks, Thierry!

He wrote:

A couple of weeks ago I bought a copy of this well-known album having a label I have never seen. Itâs a silver Chess label. I have not seen any other Berry LPs on Chess with this kind of label colour. The copy I got is the mono issue. The question is, was it also available as a stereo issue?

Reader Thierry Chanu was able to explain this unusual label:

This is one of the rarest original US issues ....... only four copies known!!!

It is the first US "DJ COPY" for this record. If you look at the label carefully, especially the side one, (use daylight and/or clean glasses) you will notice the "DJ COPY" writing.

CHESS seems to have used this bad silver paper in 1965 very briefly. Here's the label of a Ramsey Lewis Trio album on ARGO.

And to answer Morten's question: There is no stereo issue for this silver label. The company's DJ COPY/WLP records were only in mono at this time.

Morten agreed. When you look very closely at the label you may see the text DJ COPY stamped below the matrix number. Here is a detail of the silver label as well as the full standard white-label promo (WLP) DJ copy of this album.

When asked how he knows of only four copies of the silver label album, Thierry told me that this is from his own experience monitoring record offers for more than thirty years. He has seen this silver label copy offered only four times so far, one being Morten's.

Thanks, Thierry!

Monday, October 19. 2015

Chuck Berry Rarity Discovered: 1986 Live Recordings on a 1992 Keith Richards Bootleg

When Fred Rothwell's Long Distance Information: Chuck Berry's Recorded Legacy (Music Mentor Books, 2001) was published in 2001, it contained the complete knowledge about Chuck Berry's recordings known at that time. While there have been further releases of old studio recordings and some newer live recordings since then, for all experts Fred's book was complete when published.

It was kind of a sensation when in 2012 Morten Reff found a 1977 record containing recordings not included in Fred's book. And so is what I discovered some weeks ago:

I found a 1986 recording of Chuck Berry which was released on CD in 1992. And which was not in Fred's book. And not known to me or the other Berry collectors.

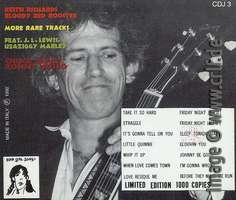

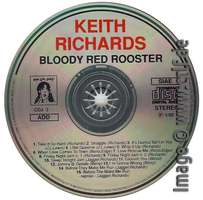

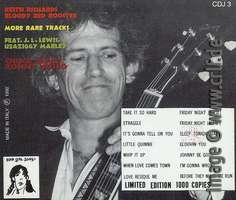

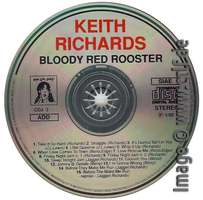

The CD is not an official one but a bootleg, though factory-produced. While the front cover says "I've been loving you too long", according to the back cover and the CD print this bootleg is called "Bloody Red Rooster". The artist is Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards playing with other artists such as Berry or Jerry Lee Lewis. The recordings have been taken from various shows.

Two songs feature Richards on guitar with Chuck Berry on vocals. They are named "Johnny Be Good" and "I'm Gonna Wrong" in the track listing, while the correct titles are "Johnny B. Goode" and "It Hurts Me Too".

The Berry recordings stem from the opening concert of the Chicago Annual Blues Festival of June 6th, 1986. This was one of the rare occasions where Berry was backed by a really good band consisting of Matt 'Guitar' Murphy, Lafayette Leake on piano, Thomas 'Tiaz' Palmer on bass and probably Casey Jones on drums. All of them were well-known Chicago Blues men. Ingrid Berry helped out singing second voice on "Baby What You Want Me To Do" and Keith Richards stepped in for the last four songs using a borrowed guitar (read story here, appr. 3/4 down the page). An audience tape of the show exists. It has poor quality, unfortunately. Likewise the two excerpts from the show included on this bootleg are of very low sound quality.

The bootleg claims that it has been released on the Bad Girl Songs label with catalogue number CDJ3, made in Italy 1992. As with all bootlegs, this may be correct - or not. Since we have no better information, we have to file this release under 1992, though.

The images show the front cover, back cover and label of the CD.

Many thanks to atsu-y and Fred Rothwell for help with this discovery and the corresponding research thereon.

It was kind of a sensation when in 2012 Morten Reff found a 1977 record containing recordings not included in Fred's book. And so is what I discovered some weeks ago:

I found a 1986 recording of Chuck Berry which was released on CD in 1992. And which was not in Fred's book. And not known to me or the other Berry collectors.

The CD is not an official one but a bootleg, though factory-produced. While the front cover says "I've been loving you too long", according to the back cover and the CD print this bootleg is called "Bloody Red Rooster". The artist is Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards playing with other artists such as Berry or Jerry Lee Lewis. The recordings have been taken from various shows.

Two songs feature Richards on guitar with Chuck Berry on vocals. They are named "Johnny Be Good" and "I'm Gonna Wrong" in the track listing, while the correct titles are "Johnny B. Goode" and "It Hurts Me Too".

The Berry recordings stem from the opening concert of the Chicago Annual Blues Festival of June 6th, 1986. This was one of the rare occasions where Berry was backed by a really good band consisting of Matt 'Guitar' Murphy, Lafayette Leake on piano, Thomas 'Tiaz' Palmer on bass and probably Casey Jones on drums. All of them were well-known Chicago Blues men. Ingrid Berry helped out singing second voice on "Baby What You Want Me To Do" and Keith Richards stepped in for the last four songs using a borrowed guitar (read story here, appr. 3/4 down the page). An audience tape of the show exists. It has poor quality, unfortunately. Likewise the two excerpts from the show included on this bootleg are of very low sound quality.

The bootleg claims that it has been released on the Bad Girl Songs label with catalogue number CDJ3, made in Italy 1992. As with all bootlegs, this may be correct - or not. Since we have no better information, we have to file this release under 1992, though.

The images show the front cover, back cover and label of the CD.

Many thanks to atsu-y and Fred Rothwell for help with this discovery and the corresponding research thereon.

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in LDI Sessionography - Updates

at

11:00

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Tuesday, October 13. 2015

The Chuck Berry Vinyl Bootlegs, Vol. 4: Telecasts

This series of articles is going to describe the Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs released in the 1970's and 1980's. For any record collector these items are important to know of, even though you don't necessarily need to have them. Omitted from all the usual discographies, information about these records is next to void. Given the secret nature of the bootlegger business there are no exact dates, numbers, or origins. I have tried to collect this information from various sources and mostly from my own collection of records. If you can add anything of worth to the information given here, I'd be glad to know!

This is the fourth part of this series and it covers a record which isn't really a Chuck Berry bootleg.

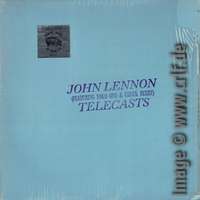

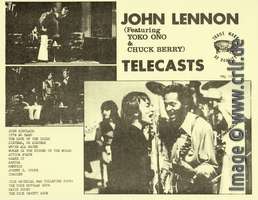

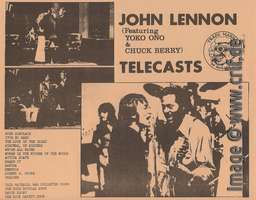

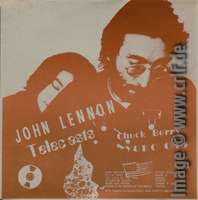

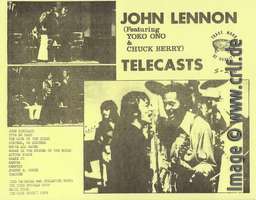

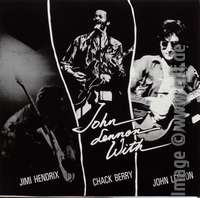

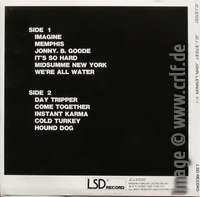

John Lennon (featuring Yoko Ono & Chuck Berry) - Telecasts - Trade Mark of Quality 71046 (and multiple other labels/numbers)

Of all bootleg records containing unreleased Chuck Berry recordings, this one is probably the best-sold and the one of which the most variants exist. This is because it's not a Chuck Berry bootleg at all. Telecasts is a John Lennon bootleg, but it contains two recordings from the Mike Douglas TV show of February 3rd, 1972. In this show, co-hosted by Lennon, the ex-Beatle invited Berry as a guest performer. Two songs were recorded, Lennon and Berry singing duets backed by Elephant's Memory and Lennon's wife Yoko Ono: Memphis, Tennessee and Johnny B. Goode. Further segments from the show such as an interview with Berry and a cooking scene did not make it to this bootleg.

During research for this article, I learned a lot about bootleg creation in the 1970's. I strongly suggest you take some time to read the excellent blog The Amazing Kornyfone Label. If you follow closely the stories of Ken Douglas, one of the most famous early bootleggers, you'll learn that research is almost impossible. They never thought about getting their acts organized in any business sense. Which makes it more or less arbitrary how the records looked like. The color of the vinyl, for instance, was more or less random. The record pressing company just used what was lying around. Even in the same production run multiple colors were used. The same with labels or covers: any color, any print. Early bootlegs had their name placed on blank covers using a rubber stamp, but if there wasn't enough time, only some were stamped, others not. Due to this, bootlegs from Ken's Trade Mark Of Quality label (and others) exist in dozens of variants and no-one can tell which ones were produced when or in which quantity. Here is what I think might be the most probable history of this Berry bootleg.

It seems that the very first version of this bootleg was produced by the legendary Los Angeles-based bootleg label "Trade Mark Of Quality". The exact date is not known, but is must have been by the end of 1972. At that time the operation was run by Ken together with Dub Taylor. They used a so-called "Farm Pig" logo on stickers, inserts, and (sometimes) labels. The initial release had a catalogue number of TMQ 71046 which was printed on an insert (xeroxed on color paper). It came in a white or colored cover with or without a rubber-stamp reading "John Lennon (featuring Yoko Ono & Chuck Berry) Telecasts". Labels seem to contain the Farm Pig logo, but also other labels exist. Note that TMQ 71046 has been copied in later years with no or little difference. This means there are bootleg copies of this bootleg.

This might be the original version of TMQ 71046:

The matrix number etched in the dead wax of TMQ 71046 reads JL-517 A/B. It's not quite clear what this number stands for. JL of course is short for John Lennon. 517 seems to be some internal numbering at TMQ. There is for instance a Bob Dylan bootleg numbered BD-516.

The letter-sized photo-copied insert on colored paper contains poor quality photos from the shows including Berry and Lennon performing together.

The tracks on this record are as follows (spelling as on the sheet):

Side 1

- JOHN SINCLAIR

- IT'S SO HARD

- THE LUCK OF THE IRISH

- SISTERS, OH SISTERS

- WE'RE ALL WATER

- WOMAN IS THE NIGGER OF THE WORLD

Side 2

- ATTICA STATE

- SHAKE IT

- SAKURA

- MEMPHIS

- JOHNNY B. GOODE

- IMAGINE

In addition the sheet tells:

THIS MATERIAL WAS COLLECTED FROM:

THE MIKE DOUGLAS SHOW

DAVID FROST

THE DICK CAVETT SHOW

Shortly after the initial release of TMQ 71046 the owners of the label (if you can call them 'owners') split and formed separated bootleg labels. Ken Douglas continued using the Trade Mark Of Quality name. These second version records show a different TMQ logo, though. While the original label had a so-called "Farm Pig" logo, the second version uses the so-called "Smoking Pig" label. Douglas re-used the original tapes to produce his own TMOQ records.

The second variant of Telecasts has the TMQ number 1834 which is etched in the dead wax. Thus a different matrix was used. It came in completely white covers. Both the insert and the labels show the Smoking Pig logo.

Concurrently with the TMQ release(s) or not much later (appr. 1973) another variant of this bootleg has been produced from yet another matrix. This time the etching reads WEC-3711. The "company" is known as Contraband Music but this name doesn't appear on cover or label. The cover is blank with a full-size insert in brown on white. The labels are white with a rubber-stamped A and B.

The original TMQ matrix with the etching JL-517 (or copies thereof) has been used very often. This record exists in a multitude of covers and comes with a multitude of labels. Here's one example of a modified insert. This version had plain green labels. This may be a later or even an earlier version. Have a look at Bob's Boots discussion of TMOQ cover and label variants of a Bob Dylan bootleg.

For more variants of JL-517 see images here (Great Live Concerts 6012-4299) and here (Box Top Records). The best known version of JL-517 is the one with the full-color photograph of the bearded Lennon sitting at a piano in front of an audience. This version also has a full-color back cover. It is this cover on which the bootleggers first forgot to list the second track from side 2 "Shake it". The song is only missing from the track listing. On the record it still is. This error has been repeated ever since.

The labels of the photograph version are blank white. Both cover and record have been reproduced often. One version has a dog label (image at discogs here). In addition JL-517 has been used to produce one of the records in two-, three- or even nine-record sets such as John Lennon - Flower and John Lennon - The Plastic Ono Box.

The full-color photo from JL-517 has also been used to produce a picture disk. A picture disk is made out of transparent vinyl with a full-size print in between the two layers for the two sides. One should note that for the picture disk an even different master has been used (probably due to production reasons). The picture disk is etched 4-A and 4AB in the dead wax.

While Telecasts was the first bootleg containing the two Lennon/Berry duets, the same recordings have been used on other, later bootlegs as well. These contain different remaining Lennon recordings, typically other duets with Jimi Hendrix or Elton John. Examples of such bootlegs are the two LP set Working Class Hero (Chet Mar CMR-75, image), the Australian two LP set Stand By Me (Toasted Records TRW-1942, see below), and the single LPs The Joshua Tree Tapes (The Kornyphone Records for the Working Man TKRWM 1803, Johnny B. Goode only, image) and John Lennon with (LSD Record JCJ-37037, again see below).

The Toasted Records cover tells that there's a third duet from the Mike Douglas show (Roll Over Beethoven). This is incorrect, though. There's no Chuck Berry on that recording. Also note the spelling of Chuck on the LSD Record cover.

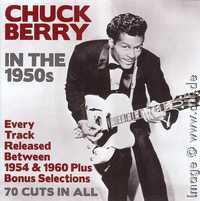

A (probably) legal release of the two songs plus the interview with questions to Berry, Lennon, and Ono was released in 2011 as a three CD set called Chuck Berry in the 1950s (Chrome Dreams CD3CD5073, 2011). You can also buy DVDs containing the complete show.

Thanks to Morten Reff for photos of the original TMQ record and the Toasted bootleg. All other images show records from my own collection.

To read the other parts of this series on Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs, click here:

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in Chuck Berry Rarities

at

15:10

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Monday, September 14. 2015

The Chuck Berry Vinyl Bootlegs, Vol. 2: Six Two Five

This series of articles is going to describe the Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs released in the 1970's and 1980's. For any record collector these items are important to know of, even though you don't necessarily need to have them. Omitted from all the usual discographies, information about these records is next to void. Given the secret nature of the bootlegger business there are no exact dates, numbers, or origins. I have tried to collect this information from various sources and mostly from my own collection of records. If you can add anything of worth to the information given here, I'd be glad to know!

This is the second part of this series and it covers a typical kind of bootleg record: a live show recording.

Chuck Berry - Six Two Five - Driving Wheel LP 1001 / Maybelline Records MBL 676

As typical for many bootlegs, the Six Two Five bootleg origins from a live show. Here it's Berry's concert for British Broadcasting BBC held at the BBC TV Theatre, Shepherds Bush Green, London, UK on March 29th 1972. Most concert bootlegs stem from professional recordings made during the concert, either cut directly from the mix or soundboard or produced for radio or TV broadcast. We don't know the exact origin of this concert recording, but the quality is high and the contents is exactly that of the original 45 minutes TV broadcast by the BBC. Thus it may have been cut from the TV transmission or directly from the edited BBC tape.

Two vinyl variants and one professionally made CD of Six Two Five exist. All show the exact same black&white photo of Berry shot from a TV screen. Also the font and placement of artist name and record title are the same. The three variants differ in the print below the photo.

Variant 1 reads Driving Wheel 1001 in the lower right corner. The lower left corner displays the Driving Wheel logo. The cover itself is blank white, the cover image is printed on a yellowish paper almost the size of the cover. The paper is glued onto the front cover.

It is not clear if the sheet containing explanations and track listing was separated from the cover initially. My copy has this sheet cut to 163x170mm and glued to the back of the cover. It has some sentences about the BBC show including the very interesting telling of a list of songs played but not broadcast. This list can only come from either the BBC themselves or from someone who was present during the original concert. Besides this, the back sheet names the album An 'S F T F' Production and lists five 'names' for which credit's due.

In addition to the sheet there's also a blue number stamped on the back cover. I don't know if this is the individual copy's number or the produced quantity, probably the former. Mine reads 00400.

The tracks on this record are as follows (spelling as on the back sheet):

Side 1

- Roll Over Beethoven

- Sweet Little Sixteen

- Memphis Tennessee

- South of the Border

- Beer Drinking Woman

- Let It Rock

Side 2

- Mean Old World

- Carol

- Liverpool Drive

- Nadine

- Bye Bye Johnny

- Bonsoir Cherie/Johnny B. Goode

While all of the songs as well as Berry's stage banter are very worth listening to, especially because Berry used a band, Rocking Horse, he had practiced with during the week before, the most interesting number is Berry's version of South of the Border, or South of Her Border as Berry puts it. This is the only song from this concert which has been released on an official record: Chess (UK) 45rpm single 6145027.

The Driving Wheel bootleg has a simple label reading only Side One / Side Two and 33 1/3 RPM. As you can see, the record is pressed in a purple-colored vinyl.

An interesting detail is the etching in the dead wax of Driving Wheel LP 1001. It reads DWLP-721-A/B. It is quite probable that 72 refers to the year of production. We'll return to this etching in a minute.

Variant 2 of Six Two Five has almost the exact same cover. The same size front sheet is now printed on white paper. The main difference is that the text Driving Wheel 1001 is missing from the lower right corner. The Driving Wheel logo itself is there, though.

The back cover is blank and to my knowledge there wasn't any insert or back sheet. The track listing is part of the record labels only.

Here you can see that this variant was released as MBL 676 on a label called Maybelline Records. Again the number 676 might point to the date of production.

As I said, it's interesting to look at the etching in the dead wax. On this record it reads DW1001A/B.

This makes it clear that this record was produced using a different, a new master disk. The reference to DW1001 makes me believe that for mastering the Maybelline bootleg they used a copy of the Driving Wheel bootleg as the source - and not the original tape.

In the early 1990's yet another variant of Six Two Five appeared. This time it was a factory produced CD. The front cover still looks the same. Only the lower parts are cut off and a label name ARCHIVIO is inserted. The catalog number is given as ARC 001. According to the print on the CD and a red stamp on the back cover this CD was Made in Italy 1991. As with all the information printed on bootlegs this is not to be taken too seriously.

By listening to the CD it becomes very probable that also the CD master was created from one of the two vinyl editions.

To read the other parts of this series on Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs, click here:

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in Chuck Berry Rarities

at

11:34

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Friday, September 11. 2015

The Chuck Berry Vinyl Bootlegs, Vol. 1: Rare Berries

This series of articles is going to describe the Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs released in the 1970's and 1980's. For any record collector these items are important to know of, even though you don't necessarily need to have them. Omitted from all the usual discographies, information about these records is next to void. Given the secret nature of the bootlegger business there are no exact dates, numbers, or origins. I have tried to collect this information from various sources and mostly from my own collection of records. If you can add anything of worth to the information given here, I'd be glad to know!

Let's begin this series with the record I use for the thumbnail of the Chuck Berry Rarities section of this blog. This may be the first Chuck Berry vinyl bootleg, or not.

Chuck Berry - Rare Berries - Kozmik KZ-501

As with most of the early bootleg records, Rare Berries did not have a printed cover but instead came in a plain white envelope. Attached were two sheets of paper which are black and white photocopies. All copies of this record I have seen so far have these sheets glued to the two sides of the record cover, so I don't know if they were delivered loosely initially. Both sheets don't have any standard paper size, so it's quite possible that they were already glued on the cover at their initial sale.

The front sheet shows a (poor) photo of Berry. He wears the colorful stage outfit he used to wear by the end of 1972 and early 1973. So this indicates a production date of not earlier than 1972. And probably also not much later as fully printed covers became common with bootlegs in the mid 1970's.

In addition the front sheet (225x292mm) tells the artist name in capital letters, the record name in all lower-case letters, the logo KOZMIK and the record number KZ-501.

The back sheet (207x283mm) repeats label, artist and record name. Next is a sentence explaining the record as "A Limited Edition album, featuring Chuck Berry's most obscure recordings, taken from the outset of his musical career." Following is a track listing and discographical details of the recordings.

The tracks on this record are as follows (spelling as on the back sheet):

Side A

- RUN AROUND

- ROLLI POLLI

- WORRIED LIFE BLUES

- HEY PEDRO

- IT DON'T TAKE BUT A FEW MINUTES

- BLUE FEELING

- SWEET SIXTEEN

Side B

- OUR LITTLE RENDEZVOUS

- DEEP FEELING

- MERRY CHRISTMAS BABY

- INGO

- HOW YOU'VE CHANGED

- BERRY PICKIN'

- BLUES FOR HAWAIIANS

As you can see from the track listing, these are not the usual bootleg recordings. Instead of unreleased studio stuff or obscure live recordings, this album contains nothing more than previously released Chess material, though some of the lesser known. But definitely not 'rare'. All of these recordings could have been found in used-record shops even in the 1970's. No later than with the release of Chuck Berry's Golden Decade Volume 3 in 1974 almost all of these tracks were commercially available even on new records. Therefore I would date the release of Rare Berries to 1972 or 1973.

There are at least two different variants of this bootleg differing by the record label print. This points to at least two production runs.

Variant 1 has green labels. The text is written with a typewriter, the label name is written using a lettering guide. The labels must have been created in haste as they even did not re-type the B side label after mistyping £ for a 5 in the record number. And on Side A they weren't even sure of the (probably conceived) label name: Where the front sheet and Side B spell KOZMIK with a Z, the label of Side A has KOSMIK with an S.

Variant 2 has a much more professional looking multi-colored label. Besides the consequent spelling of KOZMIK it also tells 'Mono', '33 1/3 RPM', 'Jewel Music' as the song publisher, and the standard saying that 'copying of this record is prohibited'. If one wouldn't know better (and would miss the cover), this could be mistaken for a legitimate release. Interesting is the hint to Jewel Music Publishing, Inc. which was Chuck Berry's publisher in the UK at that time. This could point to the origin of this record.

Both variants seem to have been produced using the same master disk. The etching in the dead wax reads 'KZ 501 A/B' on both records.

To read the other parts of this series on Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs, click here:

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in Chuck Berry Rarities

at

10:01

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Monday, August 10. 2015

Crying Steel's Third Strike - Chuck Berry and Keith Richards live 1986

I don't know the people behind Crying Steel Records, but they must be regular readers of this site.

Their first release 'Deliver Me From The Days Of Old' (Crying Steel Records CSR001, 2007) contained all of Berry's Records which I had described as being released on CD or Vinyl before but concurrently being extremely hard to find on CD. This included the Newport 1958 concert which was back then only available in Sweden or the two Japanese concerts which were at that time only available on Vinyl.

While it is doubtful that CSR001 was a legal release, it not only looked like one. It also came with a professional booklet containing many great photos and useful discographical information.

Crying Steel's second release 'Live At Winterland, San Francisco '67' (Crying Steel Records CSR02, 2014) gave us a CD copy of the three 1960s concerts which had been found in the archives of promoter Bill Graham. These had been made available for online listening through the commercial site Wolfgang's Vault, now Concert Vault. I reported on these concert in blog entries here on January 12, 2008 and on October 23, 2009.

Again it is doubtful whether Crying Steel had the rights to publish Graham's recordings of Berry's performances. But it is also not clear whether Concert Vault has the right to broadcast thise in the first place. See this recent article from Billboard.

Now I received Crying Steel's third strike: a CD called 'Long Live Rock 'n' Roll - 60th Birthday Celebration' (Crying Steel Records CSR03, 2015). Source for this CD is another concert recording available for listening at concertvault.com

I had reported on the availability of this recording in October last year in this site's chapter on Berry's 60th Birthday Celebrations. This concert was recorded on October 17, 1986 and is the second show from the Fox Theatre, St. Louis used for the preparation of Taylor Hackford's documentary called 'Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll' (released 1987). For all the details on this show read the corresponding chapter of the main site.

The Concert Vault recording of the show is about 85 minutes long. It contains most of the concert including various stage banter and impromptu jamming. To make it fit on a single CD, Crying Steel Records excluded most of the in-between talks/waits as well as some of the instrumental jams. Instead they added one more recording from this show: 'School Day' was the big finale of the show as it can be seen in the movie. It was missing from Concert Vault, though.

As no good quality first-hand recording of this final track was available, the people at Crying Steel copied it from the movie, probably from one of the commercially available DVDs. While doing so, they concurrently also extracted four other live recordings from the movie: 'No Money Down', 'Nadine', 'Almost Grown', and 'No Particular Place To Go'. These had been included in the film, but were recorded during the other of the two shows. Just like the remaining songs from the first show which were used in the film or on the soundtrack album, these audio tracks have been post-produced in Los Angeles. During this post-production some vocal parts were overdubbed. I have not yet had the time to compare the post-produced versions to the original recordings where available.

Together with the original soundtrack album, the Crying Steel CD presents a nice overview of the two Fox Theatre shows. They even added two of the Cosmopolitan Club performances also seen in the movie.

As the broadcast on Concert Vault splits the concert into individual tracks, Crying Steel made some effort to glue these parts back together. In most cases this worked quite well. Sometimes volume or cuts do not match correctly, though. They also did not notice that the introduction for Eric Clapton was included twice by error. Finally I found it irritating that at least during the Etta James segment they re-ordered the sequence of the recordings.

Again this professionally looking CD comes with a nice six-page booklet containing photos taken during the Fox Theatre shows. I really don't like the outlook of the track listing and the liner notes, though. Like with last year's release they took a strange, almost unreadable font. And the type size is so small you need a magnifying glass to read it. So, Crying Steel Records, if you read these comments, please return to the CSR001 style!

And I really wish these recordings would be released in a way that the artists, composers, and producers would get their share from the income. I'd be glad to pay.

Their first release 'Deliver Me From The Days Of Old' (Crying Steel Records CSR001, 2007) contained all of Berry's Records which I had described as being released on CD or Vinyl before but concurrently being extremely hard to find on CD. This included the Newport 1958 concert which was back then only available in Sweden or the two Japanese concerts which were at that time only available on Vinyl.

While it is doubtful that CSR001 was a legal release, it not only looked like one. It also came with a professional booklet containing many great photos and useful discographical information.

Crying Steel's second release 'Live At Winterland, San Francisco '67' (Crying Steel Records CSR02, 2014) gave us a CD copy of the three 1960s concerts which had been found in the archives of promoter Bill Graham. These had been made available for online listening through the commercial site Wolfgang's Vault, now Concert Vault. I reported on these concert in blog entries here on January 12, 2008 and on October 23, 2009.

Again it is doubtful whether Crying Steel had the rights to publish Graham's recordings of Berry's performances. But it is also not clear whether Concert Vault has the right to broadcast thise in the first place. See this recent article from Billboard.

Now I received Crying Steel's third strike: a CD called 'Long Live Rock 'n' Roll - 60th Birthday Celebration' (Crying Steel Records CSR03, 2015). Source for this CD is another concert recording available for listening at concertvault.com

I had reported on the availability of this recording in October last year in this site's chapter on Berry's 60th Birthday Celebrations. This concert was recorded on October 17, 1986 and is the second show from the Fox Theatre, St. Louis used for the preparation of Taylor Hackford's documentary called 'Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll' (released 1987). For all the details on this show read the corresponding chapter of the main site.

The Concert Vault recording of the show is about 85 minutes long. It contains most of the concert including various stage banter and impromptu jamming. To make it fit on a single CD, Crying Steel Records excluded most of the in-between talks/waits as well as some of the instrumental jams. Instead they added one more recording from this show: 'School Day' was the big finale of the show as it can be seen in the movie. It was missing from Concert Vault, though.

As no good quality first-hand recording of this final track was available, the people at Crying Steel copied it from the movie, probably from one of the commercially available DVDs. While doing so, they concurrently also extracted four other live recordings from the movie: 'No Money Down', 'Nadine', 'Almost Grown', and 'No Particular Place To Go'. These had been included in the film, but were recorded during the other of the two shows. Just like the remaining songs from the first show which were used in the film or on the soundtrack album, these audio tracks have been post-produced in Los Angeles. During this post-production some vocal parts were overdubbed. I have not yet had the time to compare the post-produced versions to the original recordings where available.

Together with the original soundtrack album, the Crying Steel CD presents a nice overview of the two Fox Theatre shows. They even added two of the Cosmopolitan Club performances also seen in the movie.

As the broadcast on Concert Vault splits the concert into individual tracks, Crying Steel made some effort to glue these parts back together. In most cases this worked quite well. Sometimes volume or cuts do not match correctly, though. They also did not notice that the introduction for Eric Clapton was included twice by error. Finally I found it irritating that at least during the Etta James segment they re-ordered the sequence of the recordings.

Again this professionally looking CD comes with a nice six-page booklet containing photos taken during the Fox Theatre shows. I really don't like the outlook of the track listing and the liner notes, though. Like with last year's release they took a strange, almost unreadable font. And the type size is so small you need a magnifying glass to read it. So, Crying Steel Records, if you read these comments, please return to the CSR001 style!

And I really wish these recordings would be released in a way that the artists, composers, and producers would get their share from the income. I'd be glad to pay.

Posted by Dietmar Rudolph

in Chuck Berry Live Tapes

at

12:11

| Comments (0)

| Add Comment

| Contact Webmaster

Wednesday, March 25. 2015

The Johnny B. Goode Session

When Fred Rothwell a few weeks ago reported here on his new findings regarding the 'who-played-on-what' questions of Chuck Berry's discography, one of the most interesting changes to the Chuck Berry sessionography was made to the personnel which created Johnny B. Goode.

The session's recording contract encountered by Tim McFarlin during his studies of the Berry vs. Johnson suit of 2000-2002 lists Johnnie Johnson as piano player for the recording session dated January 6, 1958. According to what is listed in the discographies, this is the session in which Johnny B. Goode was recorded. Formerly, Fred and other experts had listed Lafayette Leake on piano.

Fredâs sessionography change first got various comments posted here on the blog and then resulted in almost two months of (sometimes heated) discussions in email to which Berry experts from the U.S., from the Netherlands, from England, France, Norway, and Germany contributed.

In the end we had to agree that we do not agree on a common opinion. However, as this topic is of interest to most Berry collectors I will try to sum up the facts and the most important opinions.

Speaking of facts we found that we have astonishing few 'hard facts' to base any discussion or result on.

This starts with the date of the session which generated Johnny B. Goode. Depending on which source you consult the reported recording date for this song is February 28, 1958 (Michel Ruppli, The Chess Files) or December 29, 1957 (Mike Leadbitter/Neil Slaven, Blues Records). Berry's Autography has the date listed as February 28, 1958 as well. Who is correct? We have some hints:

We know that Chess Records assigned the matrix number 8633 to the final recording and mix of Johnny B. Goode. We also believe that Chess assigned matrix numbers in the sequence the master tapes were finished. The matrix numbers directly following Johnny B. Goode were assigned to different artists: The Pastels (8634/35), The Lewis Sisters (8636-40), Harvey & The Moonglows (8641-43), and so on. The next numbers assigned to Chuck Berry records are 8656/57 (A and B sides of EP 5121 Sweet Little 16), 8689/90 (side 1 and 2 of LP 1432 One Dozen Berrys). The next Berry recording Around And Around is sixty numbers after Johnny B. Goode and got the matrix number 8693. This points to at least a couple of weeks between the mastering of Johnny B. Goode and that of Around And Around. And if we assume that mastering in the 1950s was done either concurrently with the recording or soon thereafter, this also points to a couple of weeks between the recordings of the two. As a sidenote: From later sessions we know that songs recorded the same day got master numbers a dozen or so numbers off, probably because the mastering of the later songs was delayed.

Of more interest are the master numbers preceding Johnny B. Goode. They all are assigned to Chuck Berry recordings: Sweet Little Sixteen (8627), Rock At The Philharmonic (8628), Guitar Boogie (8629), Night Beat (8630), Time Was (8631), and Reelin' And Rockin' (8632). This means that all these songs including Johnny B. Goode have been mastered/recorded in one session or a set of consecutive sessions, in any case so close to each other that no other masters were made in between.

This is the reason why both Michel Ruppli and Leadbitter/Slaven had all seven songs listed as a single session. If this would be true, Ruppli's session date of February 1958 cannot be correct because Sweet Little Sixteen was already in the stores by January. Chuck Berry's list of recording sessions as published in his book places the six early songs (masters 8627 to 8632) in a session dated January 6, 1958 while he puts Johnny B. Goode (8633) along with Around And Around (8693) and five other songs (masters 8694 to 8696) to February 28.

When compiling his sessionographies, Fred Rothwell took the most probable route. He placed the recording of the consecutive masters 8627 to 8633 close together, i.e. put Johnny B. Goode close to Reelin' And Rockin'. However, because we know that the released version of Sweet Little Sixteen was take 14 and the released version of Reelin' And Rockin' was take 10, Fred had strong doubts that all these were recorded the same day. It would have been an awful long session. Therefore he used the December date from Blues Records for Sweet Little Sixteen and Chuck Berry's January date for Johnny B. Goode. These recording dates are so close together that consecutive master numbers are probable.

The session contract encountered by Tim McFarlin during his research of the legal papers filed for the 2002 lawsuit lists a date and personnel, but in contrast to later contracts it unfortunately does not give us a list of songs recorded. Thus if we believe the recording contract — and we should as the other contracts make perfect sense —, we know that a session took place on January 6th, 1958 (the date from Berry's book) and that personnel included Johnnie Johnson on piano.

Is this a proof? No, because you can argue that we don't know of a contract for a December session (yet?), that there is no list of songs, that there may be other sessions between January and March 1958 (when Johnny B. Goode hit the stores). But placing the recording of Johnny B. Goode (and maybe the others) with the January session sounds reasonable given the information we have.

Other information we have is an audio protocol of what happened at the session which generated Johnny B. Goode. The recording tapes of this session have survived and have been released to the public. So they form some additional 'hard facts' we may base our discussion on.

From the tapes we know of three tries to record the song during this session. To judge the audio recordings one has to take into account that the released versions are not labeled correctly.

The correct sequence of the recordings has been discussed here in a blog post dated July 26, 2011:

Johnny B. Goode - take 1: was first released in 1986 on CHESS CH2-92521 "Rock 'n Roll Rarities" as the second part of a track named "Johnny B. Goode — previously unreleased version".

Johnny B. Goode - take 2: is a very brief take which starts correctly but is then interrupted. This second take has been released twice: Complete with the announcement "Johnny B. Goode Take Two" on Hip-O Select's "Johnny B. Goode - His complete 1950s recordings" and without this announcement but with a false start as the first part of the previously unreleased version on "Rock 'n Roll Rarities". Note that the sequence of the two takes is reversed on the 1986 release. Also note that the Hip-O set misses take 1 completely. It is only on the 1986 double album.

Johnny B. Goode - take 3: exists in two variants. The original recording of this take without any overdubs was first released on the Hip-O Select set in 2008.

Johnny B. Goode - take 3 including guitar overdub: This is the 1958 hit version. Like on many other recordings, Berry on take 3 played just the first part of the lead guitar intro but then continued playing the rhythm guitar. The remaining parts of the guitar intro as well as further guitar solos were recorded and overdubbed later, probably during the same session.

Again this provides us with some more facts, but how much of this can be considered as 'hard facts'? The takes are introduced as takes one, two and three. Take 3 is the basis of the final released record. So we can assume that there were no other takes. The final master (8633) however is a modified version of take 3. The most obvious modification is the addition of further lead guitar segments.

Another possible modification is a manipulation of the playback speed. It is known that Chess Records modified the playback speed of Sweet Little Sixteen to make Berry's voice sound younger. When a sound recording is played faster, the pitch becomes higher with the voices sounding lighter.

With Johnny B. Goode such a modification is not as obvious as with Sweet Little Sixteen. The running times of the undubbed take 3 and of the final master are almost identical. Whereas we have to keep in mind that we have access to the final master only in the form of 45 rpm records and digital copies like the one on the Hip-O Select box.

Just for academic purposes (and without any other use anyway) I have created myself an audio file in which one can hear the beginning of both variants of take 3 of Johnny B. Goode. The left stereo channel is the un-modified take 3, the right stereo channel contains the released master. One notices the overdubbed guitar which is now to be heard on the right channel only. And one can notice that there is a tiny difference in speed. It sounds as if the released master indeed has a slightly higher pitch and runs a little bit faster.

[I have asked Universal Music for permission to provide readers with a download link to this audio file. I have not received any permission nor any response at all, though (yet).]

What does this tell us about the recording session itself? Very little. We have no information when the guitar overdub was recorded and how. In the late 1950s there was no multi-track tape recording at Chess. Thus it is probable that the original take was played back into the studio where Berry then added the missing guitar lines. This is also where the speed difference may come from: The tape played back on a different machine and then re-recorded along with the solo guitar.

All we can tell for sure is that the mastering of the overdubbed take happened in temporal proximity to the mastering of Sweet Little Sixteen which in turn obviously happened before that song's release in January 1958.

In regard to the discussion on who was the pianist on Johnny B. Goode the differences between the three takes are relevant. Comparing the takes, it is obvious that Berry pretty much knew how he wanted the guitar to sound like. The main difference between the complete takes 1 and 3 is the piano playing. And how important this piano playing was becomes audible from the discussions taking place during take 2.

Take 2 starts just normal with the famous guitar intro. Then, when the piano comes in, someone shouts "hold it" and a dialog starts which I interpret as follows. To better understand the different sentences, I created another sound file in which I tried to level the loudness of those said through a microphone and those said without.

[Again I wanted to provide a download link to this sound-enhanced excerpt just for academic purposes but did not hear from Universal Music as the owner of this recording.]

I hear this dialog:

Voice 1 'Hold it, hold it, hold it!'

Voice 2 'What do you want, Jack?'

Voice 1 'You were making Roll Over Beethoven on piano that time, stay away from that!'

Voice 3 'Piano or guitar?'

Voice 2 'Keep playin' on the guitar during the solo.'

Voice 1 'Yeah, on the solo he was makin' Roll Over Beethoven. Stay away from that one!'

Voice 4 'Who is (he talking to)?' interrupted

Voice 1 'Johnny B. Goode, take three'

It is not clear which voice belongs to which person. In my opinion Voice 1, the main voice (on the microphone), is the voice of Jack Sheldon Wiener, engineer and from May 1957 to August 1958 co-owner of the recording studio at 2120 S. Michigan Av., Chicago. Jack is referenced and talked to in other segments from this session, e.g. in talks related to Sweet Little Sixteen and Reelin' And Rockin'. Voice 2, who instructs Berry to continue playing guitar during the piano solo, seems to be Leonard Chess. This fits to Berry's recollections of the session in his book where he writes: "Leonard Chess took an instant liking to this song and stayed in the studio coaching us the whole time we were cutting it." Voice 3 must be one of the musicians. Since he has no microphone I suspect this is the pianist asking. Voice 4 finally sounds like Chuck Berry to me.

Wiener obviously noticed that the piano solo on take 1 was too close to what they had released as Roll Over Beethoven. Berry himself did not care that much. He believed anyway that his songs differed in lyrics and solos alone. The rest was just standard. "Roll Over Beethoven, Johnny B. Goode, you name it, all of the songs could carry the same background or music that each other has." (Berry quoted by Tim McFarlin, see blog post of December 18, 2014)

I admit that both my interpretation of the studio dialog and my assignment of persons to voices is subject to discussions. The other Berry experts who listened to this studio talk had various different opinions. Some assigned Voice 1 to Leonard Chess, some even to Berry himself. Bob Lohr, who played piano behind Chuck Berry for the last decade, says:

The cat who stated "You were playing 'Roll Over Beethoven' ... stay away from that", and "he was playing 'Roll Over Beethoven' on piano" ... is clearly Chuck, not the engineer ... he's using the in-studio high quality vocal microphone and I'm 1000% sure it's Chuck ... after 18 years, I know his speaking voice like the back of my hand ... furthermore, the way Chuck pronounces "Beethoven" is pretty unique ... trust me, on my life I'm telling that was Chuck speaking, end of story!!! The engineer and LC [Leonard Chess] are speaking through the low quality studio talkback microphone.

I perfectly accept that Bob can identify Berry's voice as it sounds today. We should not forget that we are talking about a recording made when Berry was in his early thirties. Voices change and to me the instructing voice and the voice singing sound differently.

The main question the discussions about Johnny B. Goode circle around is the question "Who is the pianist instructed to stay away from playing Roll Over Beethoven". Some Berry experts point to Ellis "Lafayette" Leake, others favor Johnnie Johnson. Early discographies had listed Leake on piano, the ultimate discographical authority Fred Rothwell now lists Johnson as pianist — following the January 6 recording contract. It is unknown how the early discographies came to listing Leake. Fred writes in a recent article for "Now Dig This" magazine:

Session information about musicians has grown organically over the years and much of it has been based on anecdotal, word-of-mouth remembrances. In the '60s, blues fans would ask artists about old sessions and I'm sure guys like Willie Dixon, for instance, would try to placate them by giving info that was not always correct. Lafayette Leake was a big friend of Willie's and, I suspect, he got named as pianist for wont of someone else at times. Johnnie Johnson was not part of the Chess studio clique (he never recorded in his own name at Chess) and I think he may have been overlooked.

Those who favor Leake also say that both Berry and Johnson have denied many times over the years that Johnson was among the staff recording Johnny B. Goode. However, I was not able to find a single source for this claim. The only source to this effect is from Travis Fitzpatrick's biography of Johnson where he cites Johnnie saying "The only recordin' I didn't play on was 'Johnny B. Goode'. Chuck did that as a surprise for me."

Asked about this quote by Tim McFarlin and me, Travis said that when using Johnnie's quotes one should always keep in mind that Johnnie's interpretations and those of the reader might not necessarily match. The whole lawsuit between Berry and Johnson was based on the fact that to Johnson "writing music" was something completely different than what a copyright lawyer would understand thereunder.

Likewise, Johnson's saying that he did not play on Johnny B. Goode may not necessary mean "play piano", but more to the effect of "play a role" meaning "I did not contribute to Johnny B. Goode which I didn't know about before we went into the studio.".

In an 1999 interview with Ken Burke for the Rockabilly Hall of Fame (see http://www.rockabillyhall.com/DrIJJohnson.html) Johnson became more specific:

That's how we worked out all the tunes that's he's [Chuck Berry's] got practically, except "Johnnie B. Goode." I had nothing to do with that, that was sort of a tribute to me, I understand.

This is from Travis:

Since he is no longer around to clear it up, I can only guess what Johnnie meant with his original statement about not playing on "Johnny B. Goode." I probably should have questioned him more about it before he passed away. Remember, this is the man who said, "I didnât write the music with Chuck, I was just in the room sometimes when he was writing" before describing the process he and Chuck used to write their music! It was years before we understood the reason why he said this. Johnnie believed writing music meant writing down lyrics or transcribing notes onto a lead sheet. Johnnie called what he and Chuck did "making up music" because it wasnât written down. If you ever saw the movie Forrest Gump, that was very much how Johnnie viewed the world. As a consequence, more misunderstandings are coming to light. For example, Johnnie didnât think he played on the early Mercury sessions because he thought the re-recording of all their Chess hits was due to a fire at Berry Park destroying the originals. He thought Chuck arranged to re-record the old songs on his own! That was Johnnie in a nutshell.

Whether or not Johnson or Leake played piano during the Johnny B. Goode session is still open to discussion. One would think that people who know Johnson's playing well can simply hear whether it's him playing. In the same 1999 interview Ken Burke asked Travis Fitzpatrick: "Even as low in the mix as some of Johnnie's piano work is, would you know his playing when you heard it?"

Travis replied:

Sure. I can always tell his playing. [...] I can listen to a lot of those songs and tell it's him. When I listen to some of those original Berry records I can say "That's Johnnie for sure!" I can tell that Lafayette Leake came in on some stuff, especially "Johnnie B. Goode." I can tell that's not Johnnie. Then, like he was saying, there's this whole thing where Leonard Chess would come in during his solo and run his hand up and down the keys, which Johnnie never does. So, that kind of made it more difficult, plus Lafayette Leake was a very good mimic. [...] But I'm 100% sure that was Lafayette Leake on "Johnnie B. Goode."

Another expert on Johnnie's piano playing is Bob Lohr. Bob is a pianist himself and has played with both Berry and Johnson. He likewise claims that he can identify Johnson's playing, too:

I'm extremely familiar with JJ's [Johnnie Johnson's] style. I have been called upon here in local studios over the years to 'clone' or mimic JJ's style on different projects as JJ's style is pretty much ingrained in my musical DNA. Based upon my familiarity with JJ's style, I would have to say that it was clearly LL [Lafayette Leake] instead of JJ on JBG [Johnny B. Goode] based upon style alone. The stylistic differences between LL and JJ makes me sure that LL was the man on the keys despite the union log of the date. They both played in a similar boogie/blues mode behind Chuck (and often on the same out-of-tune piano apparently!!!), but Leake ... with all due respect to JJ ... was a far more fluid and accomplished jazz player and generally threw in some nice fat jazz double-hand chording at the end of his solos ... something that JJ rarely if ever did. You'll hear Leake do this throughout Takes 2/3 and on the final take as well.

Interestingly, both experts did not know that take 1 of Johnny B. Goode existed which has a very different piano playing and was released only on the 1986 double album. When I asked them to re-check take 1, Bob Lohr found: "You are correct in that it sounds a lot like JJ's style, although I can still hear the stylistic difference."

Travis Fitzpatrick was even more astonished:

I must revise my opinion (an ultimately my book) concerning Johnnie Johnsonâs playing on "Johnny B. Goode." Until Dietmar pointed it out, I did not realize that take one was misplaced as take three on Rock 'n Roll Rarities. Consequently, I never really listened to it. Well believe me ... I have now listened to it. I listened to that first take of "Johnny B. Goode" for hours last night. My immediate reaction was "Holy COW! The AFM contract was right! That is Johnnie Johnson!" Just to be sure, I jumped into my Johnnie recordings both issued and unissued and found examples of every lick. His phrasing and the way he resolves his licks is Johnnieâs fingerprint. It is him. The flashiest lick has been right under everyoneâs nose. Watch the rehearsals for "Carol" in Hail Hail Rock and Roll or better yet, Johnnieâs backing behind the sax on "Almost Grown" in Hail Hail Rock and Roll. Those songs are in C and G respectively, but you can see that the lick is in his repertoire and in fact, he uses it quite a bit. Just not on most of the Chuck Berry recordings — which is why it hasnât become recognized as a standard JJ lick.

Travis' remark on the song keys is significant because Johnny B. Goode is written in B flat (Bb). Bob Lohr again:

It's harder to play Chuck's style (or blues in general) in the flat keys ... E flat (Eb) or B flat (Bb). Johnnie was not too good at playing in those keys and would never use those keys when playing in his own band. LL on the other hand, was technically a much more accomplished classically-trained/jazz player who could play almost as well in Bb or Eb as JJ could play in G. JJ could certainly play in B flat or E flat, but nowhere near as well and as fluid as LL plays here in B flat. If in fact JJ played on JBG, he played in a completely different style which we have never heard before or since from JJ ... and better in B flat than he ever played before or since.

Bob's statements about Johnson's facility in playing jazz licks or playing in B flat at all had Travis to disagree: